Urban planning is a tricky discipline where an idea’s outcome is often evident only years after its implementation. A few years ago, the city moved to ostensibly “correct” a perceived decades-old planning concept, yet time will tell whether they’ve stumbled into an even worse blunder by allowing developers to gobble up public space which was once created in exchange for extra buildable footage. The first test may soon come at 7 Hanover Square, to be rebranded as 100 Pearl Street, where GFP Real Estate plans to replace open-air public space with an enclosed lobby and food court.

In the 1960s, New York’s new zoning code allowed developers to build public plazas (“Privately Owned Public Spaces,” or POPS) in exchange for extra air rights. As long as the space was cleverly designed, everyone benefited - the builder got extra building footage while the public had more of the outdoors to enjoy amid skyscraper canyons.

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

“Clever design” has proven to be the crucial caveat among the dozens of POPS that have been built in the years since, which amount to 80 combined acres. Depending on their design, the Municipal Art Society classifies POPS into five categories that range from “destination,” which readily attract visitors, all the way down to “marginal,” which tend to be underperforming and downright dreary. A 2007 report revealed that only 16 percent of POPS were considered “destination” spaces while a whopping 41 percent were of “marginal” use.

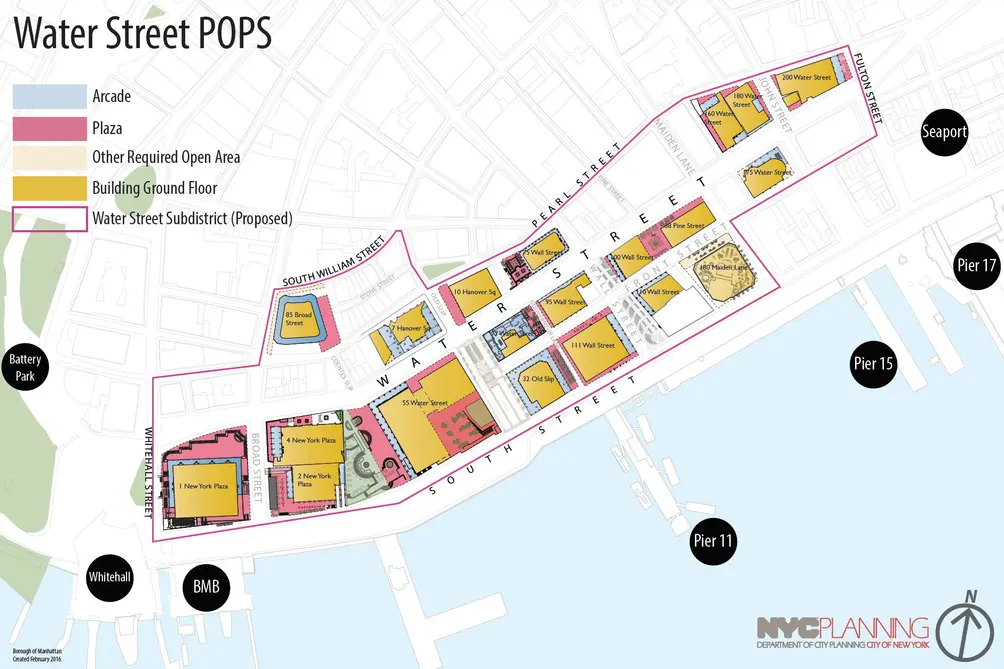

To work with the Financial District’s small blocks and narrow Colonial-era streets, the city allowed new buildings on and around Water Street to feature covered arcades - open-air spaces with office floors above. Arcades are a cherished traditional typology with millenia-long European roots (Rue de Rivoli in Paris is a fine example). In post-war Downtown, however, many such arcades fell victim to ill-conceived layouts and planning, with foreboding, poorly-lit, barely useful spaces. Of the 23 POPS analyzed along the Water Street corridor, only two ranked as “destination” spaces and four more as “neighborhood,” with the remaining 17 falling into the three lowest categories.

Privately owned public spaces (POPS) around Water Street. Credit: the City of New York

Privately owned public spaces (POPS) around Water Street. Credit: the City of New York

Privately owned public space at 7 Hanover Square. Credit: the City of New York

Privately owned public space at 7 Hanover Square. Credit: the City of New York

7 Hanover Square public arcade. Credit: Google

7 Hanover Square public arcade. Credit: Google

In 2016, the de Blasio administration allowed building owners to convert open-air arcades into indoor commercial space, turning a “shadowy, windswept realm into moneymaking retail,” as per a New York Times article. However, the amendment is troubling because instead of incentivizing owners to improve poorly-planned public space, it outright gives it away for private commercial conversion.

The NYT report calls the practice a “double dip” that allows landlords to “receive a benefit from new retail space on top of the revenue they already get from the bonus office space,” and quotes local architect Alice Blank stating that the amendment “violates the deal made with the citizens of New York, when developers got prime additional real estate in exchange for their unqualified promise to preserve this public space.” 6sqft states that “opinion is divided” on the “controversial” amendment, while Curbed minces fewer words, questioning whether the move is a “shameless land grab.”

The project planned at 100 Pearl Street, a 27-story, 846,463-square-foot Postmodern office tower built in 1983 (until recently owned by Milstein, which also owns a large development property nearby at 250 Water Street), would be the first major arcade conversion since the controversial amendment’s passage and may serve as an early litmus test of its viability. Today the public space at 7 Hanover consists of a covered arcade along Water Street and Hanover Square and a cavernous through-block arcade between Water and Pearl streets. Near the end of last year, GFP Real Estate filed applications to replace both the public arcade and passageway with a private lobby and a dining concourse.

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

7 Hanover Square. Credit: S9 Architecture

On one hand, the plan looks promising. Renderings by S9 Architecture, which did as well a job as could be under the plan scope, show a brooding arcade replaced with an airy, glassed-in lobby, while the dark through-block passage becomes an action-filled food court, a welcome amenity in an increasingly round-the-clock neighborhood. However, the move also shutters an important public walkway that connects the waterfront to the cafe-lined Stone Street district and significantly reduces the size of the public plaza outside the building, even if it adds new seating to the remaining rump plazas.

Another wildcard in play is the type of development that would eventually come to the next-door site at 46 Water Street, which has been shrouded in netting for several years for its impending demolition.

But even if the private shopping mall that replaces the public plaza at 7 Hanover Square proves to be a local favorite, if other building owners follow suit, a sizable chunk of FiDI stands to lose a unique, if imperfect, character of its public realm.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.