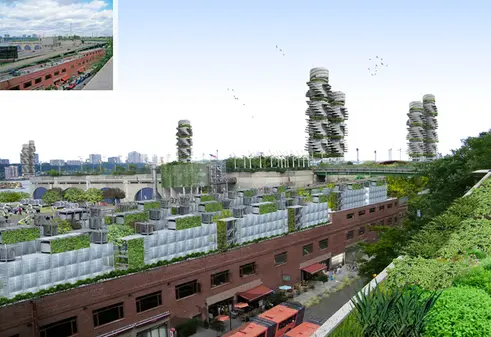

Vertical farms in mid-town Manhattan to produce food for up to 30,000 people? Renderings credit of Terreform led by Michael Sorkin https://www.terreform.info/nycss

Vertical farms in mid-town Manhattan to produce food for up to 30,000 people? Renderings credit of Terreform led by Michael Sorkin https://www.terreform.info/nycss

On April 2, Michael Sorkin, unchained architect, urban theorist, and author passed away

in New York at age 71 after contracting COVID-19. Among his many roles focused on improving civic life for all, Sorkin served as director emeritus of the Graduate Urban Design Program of the City College of New York (CCNY) and as a long-time architecture critic for the Village Voice. He leaves behind his wife, Joan Copjec, and an invaluable body of work to be carried on by his New York-based practice Michael Sorkin Studio.

At a time when COVID-19 catapults all urban centers towards an inflection point, the only future guaranteed is no city will return to their 2019 'normal.' We revisit one of Sorkin's NYC-focused plans, designed in collaboration with Terreform, which calls for a self-sustaining city that uses design and planning principles to improve peoples’ lives and well-being.

Rendering of Amsterdam Avenue as a productive street.

Rendering of Amsterdam Avenue as a productive street.

Called New York City (Steady) State, the vision is among Sorkin/Terreform's many studies in promoting possible alternative visions for our built environment. Released shortly after Superstorm Sandy, it asks if New York City could become self-reliant in areas such as food, energy, waste, water, air supply, manufacturing, employment, culture, health, and transportation. Now especially relevant considering the pandemic's disruption to our globalized supply chain, the plan ponders if 100% self-sufficiency is possible for the city. If the ecological footprint of the city can become equivalent to that of its political boundary.

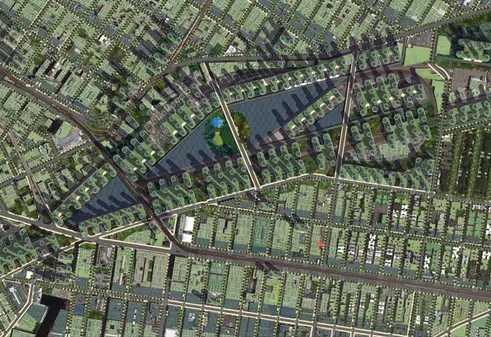

Vertical farms in Sunnyside Gardens, Queens. The controversy that would ensue would give new meaning to Not In My Backyard

Vertical farms in Sunnyside Gardens, Queens. The controversy that would ensue would give new meaning to Not In My Backyard

Vision for Sunnyside Yards

Vision for Sunnyside Yards

Riverbank State Park and Hamilton Heights' Hudson River waterfront

Riverbank State Park and Hamilton Heights' Hudson River waterfront

Complete self-reliance proved impractical given the amount of space and energy required for nearly 8.5 million people. But Sorkin did suggest that up to 30 percent of food production could be accomplished given some dramatic urban interventions as seen in the images above. One could debate how well a self-reliant city could handle a pandemic such as COVID-19, especially if the locality's workforce suddenly was not able to meet their demand. Nevertheless, a greater takeaway from Terreform's plan is how it envisions ways that a more involved and self-reliant citizenry could better serve their own social, environmental, and economic needs, in turn improving their local community and personal well-being.

With headline stories such as Escape from New York providing anecdotal evidence that dense urban living and public transit are leading factors in the spread of the pandemic, ex-urbanites now have new fuel to justify the belief that living in dense urban centers is wrong and unnatural.

Even prior to COVID-19, things weren't so rosy for New York City. With Amazon eviscerating our once unparalleled physical retail diversity, empty investment apartments and out-of-reach housing costs that provide a fraction of what could be attained elsewhere, and a criminally underfunded public transportation system that was already a daily psychological challenge to endure. Moreso, with many New Yorkers primarily confined to their apartments for over a month, those of us not fortunate to afford access to a terrace, balcony, or roof deck, the walls of our so-called shoebox-sized apartments now seem harder to defend.

But even in this precarious state the city has drifted into over the last decade and a half, the fundamental appeal of urban life lives on. Local is almost always better, and in Sorkin's 2013 text "Twenty Minutes in Manhattan," he calls for a return to a more authentic urbanity, “a city based on physical proximity and free movement and a sense that the city is our best expression of a desire for collectivity.”

Frolicking, observing and participating in the communities around us still remains more enjoyable than sitting in a car driving from one strip mall lot to a home garage; and as Sorkin writes, "Our sense of citizenship and belonging are not the product of ownership but of affinity, interaction, and social reciprocity.”

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.