Bird's eye view (Handel Architects)

Bird's eye view (Handel Architects)

Over the last 50 years, New York hasn’t had much luck in realizing innovative residential schemes, and even less fortune adapting technological advents and urban lifestyle changes into building code and zoning. Rather, we leave it up to our compassionate developers, who for the most part shower the top of the market with trendy amenities and lifestyle frills while shooting for the bottom of the barrel for the masses.

With our wealth of design talent, bold schemes have certainly put forth, but what has been built is almost always practical — venturing into banal when earmarked for the middle and lower classes. Even worse, to solve our affordability crisis, tax dollars are often shoveled towards repetitive and unimaginative designs that detract from the existing housing stock and after a winter season appears tired, rusted, and ill-maintained — giving occupants little reason to take pride in their domiciles or neighborhood.

With our wealth of design talent, bold schemes have certainly put forth, but what has been built is almost always practical — venturing into banal when earmarked for the middle and lower classes. Even worse, to solve our affordability crisis, tax dollars are often shoveled towards repetitive and unimaginative designs that detract from the existing housing stock and after a winter season appears tired, rusted, and ill-maintained — giving occupants little reason to take pride in their domiciles or neighborhood.

This wasn’t always the case, of course, it was our city that raised the standards of tenement housing, first legalized and embraced fire-resistant high-rise living, and went head-first into Modernist urban renewal schemes and suburban tract housing (the latter two is likely where the distrust of architects and planners began). While their hearts may have been in the right place (or were they?) many of these utopian visions have become worse centers of delinquency, vandalism and general social hopelessness than the slums they were supposed to replace, as Jane Jacobs puts it.

In this article:

Recent experimental housing schemes in NYC: From L to R: The co-friendly Via Verde, Carmel Place, and 461 Dean Street (Max Touhey)

Recent experimental housing schemes in NYC: From L to R: The co-friendly Via Verde, Carmel Place, and 461 Dean Street (Max Touhey)

Mistakes of the past are no reason to write off the future, however. And the impetus for new ideas still broaches the surface occasionally. Lessons from recent and exceptional one-off, government-led pilots such as Via Verde and Carmel Place have mostly served as political photo-ops and filler of design magazines than to seriously rethink the way we build housing. With the scarcity of urban housing at its most severe, now appears to be an ideal time to (re)consider innovative, efficient, and environmentally-sound ways to provide “affordable” housing to the masses and to legislate what works into code.

85 Jay Street's incredible location (Kushner Companies)

85 Jay Street's incredible location (Kushner Companies)

One opportune site for experimentation is 85 and 95 Jay Street in DUMBO. The full-block property was sold to Kushner Companies with CIM Group and LVWRK by the Jehovah’s Witnesses in 2016. While the $345 million cost of the lot surely does not encourage any out-of-the-box thinking and regulations governing the lot do not mandate any kind of affordability, the property’s size and location in one of the city’s most sought-after neighborhoods presents a unique opportunity to build something radical.

While renderings of the final design have yet to be released, building permits were filed last November, and from what we can gather, there will be both rental and condo apartments spread across four sectors, A, B, C, D. Thankfully, at grade there will be several retail spaces and a courtyard that we hope will be publicly accessible. Nonsensically, thanks to zoning requirements, there will be 712 parking garage in its sublevel despite there being two subway stations nearby.

The permits list Morris Adjmi Architects as the architect of record. While not known for their avant-garde prowess, to the relief of some, the firm has shown some tasteful flare in their designs for 837 Washington in the Meatpacking District and the Gothic-inspired tower 30 E 31 in NoMad. We do fear, however, that 85 Jay will manifest into another palatable, retro-industrial enclave for the wealthy, with an insular package of amenities, panoramic views of the skyline and blah, blah, blah. Yes, we are still holding out hope that DUMBO becomes more than TriBeCa on the East River.

View from Manhattan side of the East River (Handel Architects)

View from Manhattan side of the East River (Handel Architects)

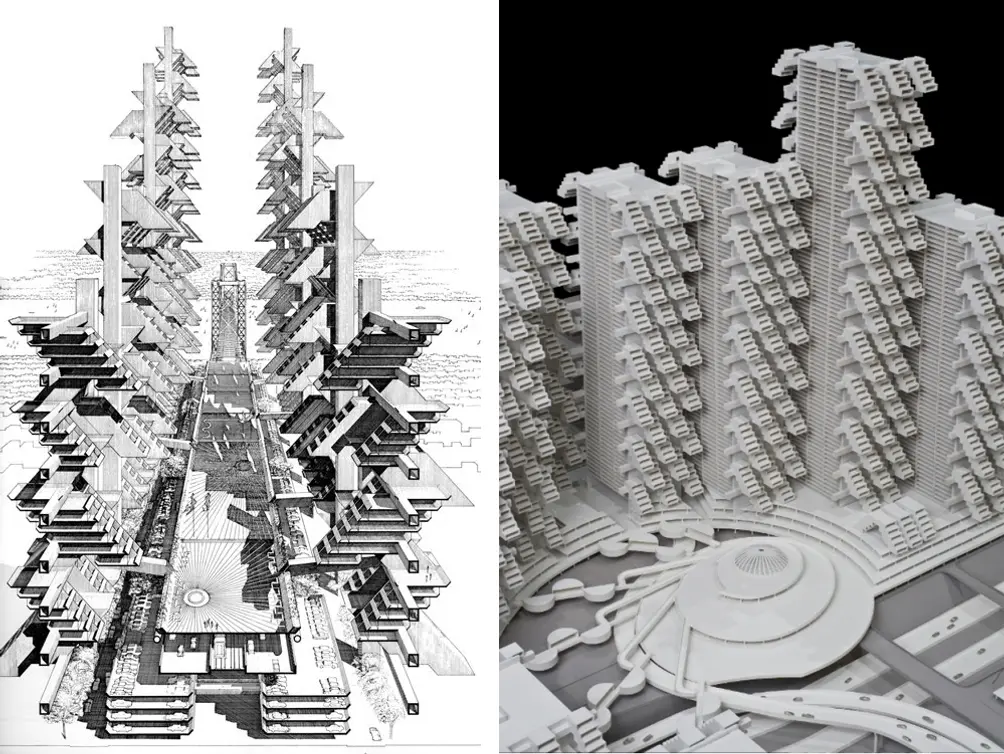

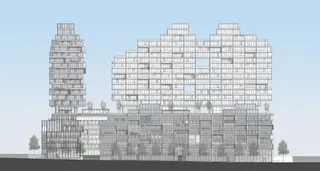

To remain optimistic, we look to Handel Architects’ apparently unchosen design for 85 Jay Street. Their take on the 1.1 million-square-foot opportunity proposes a school and hundreds of residential units encircling a central public courtyard. As an homage to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 in Montreal, residential modules shift in and out along the facade, creating a bounty of terraces and outdoor spaces throughout its 25-story rise. Rather than having a unified floor of communal spaces, lawns, tennis courts, and a swimming pool are peppered throughout the complex. As for its dropped-from-space appearance, instead of aping the surrounding former industrial warehouses, context is shown through scale. A nine-story wing will face Front Street and the DUMBO Historic District, while the towers rising inland, hopefully blotting out the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Rendering of Handel Architect's proposal of 85 Jay Street in DUMBO (Handel Architects)

Rendering of Handel Architect's proposal of 85 Jay Street in DUMBO (Handel Architects)

Safdie hoped that Habitat 67 would revolutionize affordable housing and jump-start a wave of prefabricated modular development. It was designed to marry the benefits of suburban living—namely gardens, fresh air, and privacy —with the economics and density of urban high-rise living. Today, Habitat is by no means affordable — ironically, its novel design made it less so — and fifty years later, we’re still working out the kinks of vertical modular construction. The city’s first and only modular residential high-rise at 461 Dean Street has had less than a smooth delivery to say the least.

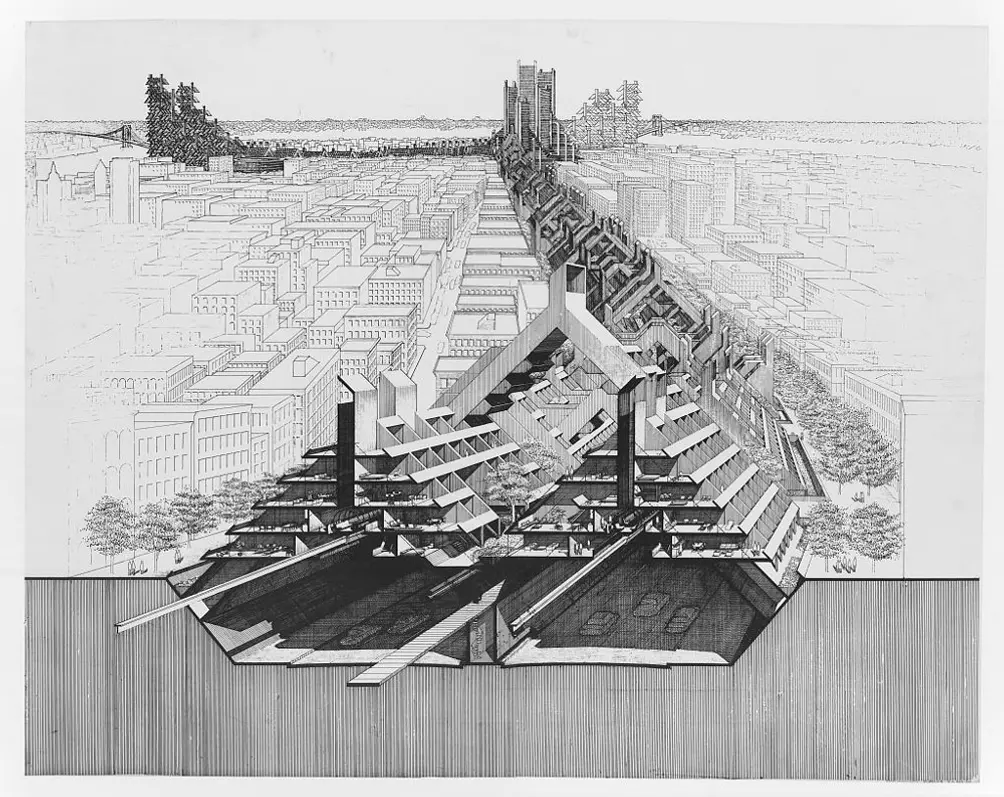

The inspiration for the project, Habitat 67, echoes a little known post-war Japanese architectural movement called Metabolism, where its proponents believed that buildings should be designed as living, organic, interconnected webs of prefabricated cells. Sadly, New Yorkers are not bees and due to our spontaneity, living within a methodical hive is usually not our urban living preference of choice. New York has had several of these types of mega-structures planned, and are now widely looked upon with much derision by non-architects. i.e. Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway towers and a similar scheme for Battery Park City. Terrifying indeed.

Paul Rudolph's towers along the Robert Moses-proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway (Cooper Union)

Paul Rudolph's towers along the Robert Moses-proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway (Cooper Union)

Paul Rudolph's LoMex design via Paul Rudolph Foundation

Paul Rudolph's LoMex design via Paul Rudolph Foundation

Handel does not specify whether their energetic, Tetris-esque vision would have utilized modular construction, though the city’s sole pre-fab company, Full Stack Modular has its factory nearby in the Navy Yard. A recent story from the Real Deal hints that the city’s modular salvation may be near. Reportedly, Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen says that the city aims to “crack the code” on mid-rise multifamily development, in the hopes, this will be “a new chapter for modular.”

Elevations via Handel Architects

Elevations via Handel Architects

While the “eaten-away,” tumor-like aesthetic seen in Handel’s project is mostly eye candy and might not be everyone’s favorite (we’re not totally convinced either), it’s hard not to admit that the complex looks like a rather interesting and enjoyable place to live, at least compared to the run-of-the-mill "luxury" high-rise across the way at 100 Jay Street. The scheme recalls some of ODA New York’s work, namely their unselected design for a similarly-scaled complex for the Gowanus waterfront. The smattering and scattering of outdoor perches also resembled Bjarke Ingels’ 8 House in Denmark where various elements of an urban neighborhood are stacked into layers and connected by leisure spaces. And if his designs are fit for the happiest countries in the world, why not here in our supposedly progressive city. We all could use a bit more cheer.

View north up Bridge Street (Handel Architects)

View north up Bridge Street (Handel Architects)

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.