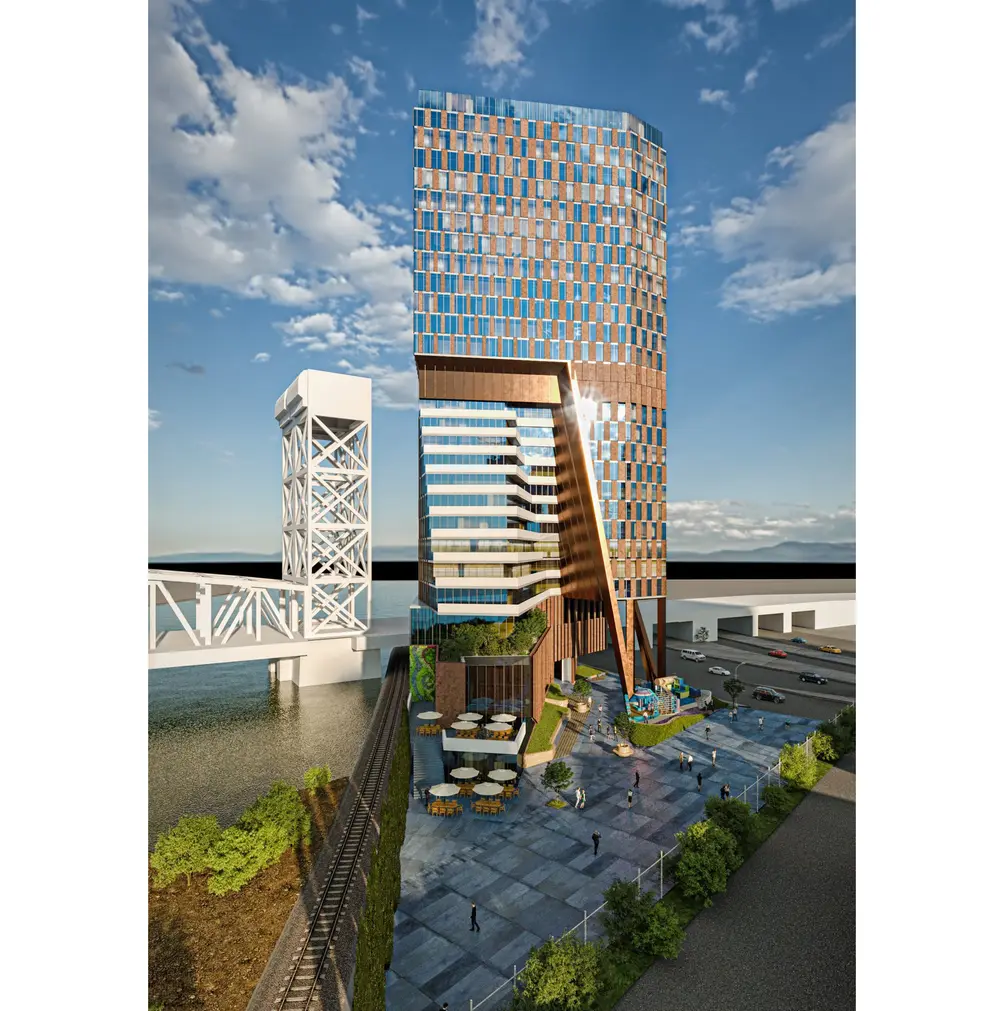

Paragon, a new residential high-rise planned on the Long Island City waterfront (ZD Jasper)

Paragon, a new residential high-rise planned on the Long Island City waterfront (ZD Jasper)

Updated 11/22/2024 with the latest votes and updates to City of Yes for Housing Opportunity

The week before the Thanksgiving holiday, two New York City Council committees approved Mayor Adams’ "City of Yes for Housing Opportunity." The land use committee approved it by 8-2, but the zoning subcommittee cast a more narrow 4-3 vote. Moreover, the Adams administration has committed $5 billion to the proposal: $1 billion for housing development, $2 billion for infrastructure improvements related to the new housing, $1 billion for expense funding for tenant protections, and $1 billion in state funding for housing capital.

In this article:

The ultimate deal included some compromises that disappointed progressive City Council members and activists. As a result of these compromises, the original estimation of over 100,000 new housing units over the next 15 years got revised down to approximately 80,000. However, it nevertheless comes at a time when renters and buyers are facing low inventory that cannot help but drive prices up, and represents the most substantial changes to the city’s zoning code since it was established in 1961.

After the City Planning Commission approves the revised plan, the full City Council is expected to vote on it in early December 2024. As we wait to see how this plays out, we take a look at the initial changes proposed in "City of Yes" and the compromises presented.

Midtown skyline from 330 Wythe Avenue, 5J in Williamsburg (Compass)

Midtown skyline from 330 Wythe Avenue, 5J in Williamsburg (Compass)

#1. Universal Affordability Preference

The new Universal Affordability Preference tool will allow buildings to add at least 20 percent more housing units, but only if the units are considered "affordable." While this may sound like a great idea, it is also where the "City of Yes" remains a bit fuzzy. City councilors maintain that "affordable" means that a family of five looking for a three-bedroom would not pay more than a third of their family income on rent, but what does this look like in reality?Let’s say you have two local high school teachers with a combined income of approximately $140,000 annually looking for a home for themselves and their three young children. A third of their gross income would be roughly $46,000 annually, which means an “affordable” three-bedroom unit is anything under $3,900 monthly. Although a three-bedroom under $4,000 would represent a deal in the current market where the average price on a Manhattan three-bedroom is over $9,500, whether such an apartment is truly affordable to a middle-class family is questionable.

After taxes and other deductions, the monthly take-home pay of a couple making roughly $140,000 in New York City is likely closer to $7,000. This means that in reality, the couple would still be spending roughly half or more than half of their take-home pay on housing and the rest on transportation, childcare, food, recurring bills, and other basic necessities.

Some activists were heartened by the idea of more housing, but are concerned that it will not be truly affordable. One of the City Planning Commission members who voted no objected on exactly these grounds (h/t City Limits). The same volume of new housing is allowed under the modified plan, but it is required to be affordable to households earning 40% of the Area Median Income.

Construction in 2023 of the mixed-use rental complex Society Brooklyn and Sackett Place set along the Gowanus Canal. (Image courtesy of Urban Ateliers Group and Property Markets Group)

Construction in 2023 of the mixed-use rental complex Society Brooklyn and Sackett Place set along the Gowanus Canal. (Image courtesy of Urban Ateliers Group and Property Markets Group)

#2. Office to residential conversions

Since the pandemic emptied out many office buildings, there have been calls to convert empty and underused office buildings into residential buildings. In response, the "City of Yes" plan includes several zoning bylaw updates that, in theory, will speed up conversion efforts. In the meantime, the City has also launched a “one-stop shop” for owners interested in converting their properties. This aspect was largely left unchanged in the modified plan.It is important to note, though, that converting office buildings into residential buildings is easier said than done. While Mayor Adams and his team estimate that office-to-residential conversions could produce up to 20,000 new units of housing for 40,000 New Yorkers, the cost of and likelihood of these conversions happening remains uncertain. Due to the large floor plates found in most office buildings, which require fewer windows and air shafts than residential units, conversion projects, if they are possible at all, are nearly always costly and complex to complete. As such, even with such initiatives, many architectural engineers believe that only a small portion of local offices will ever be successfully converted into residential units.

#3. Town center zoning

Across New York City’s five boroughs, residential units can be found above commercial properties. With the launch of “City of Yes,” more residential properties will be permitted above existing commercial properties. The hope is that this initiative will bring more housing to major transit corridors, helping to increase housing and public transit usage. But for this plan to work, a high percentage of developers will need to determine that constructing low-rise residential buildings on and near transit corridors is a good investment.The modified plan allows two to four stories of housing above storefronts in some commercial zones. However, this will not be allowed in single isolated commercial blocks, nor in areas mostly developed with one- and two-family homes.

#4. Removing parking mandates

Starting in the 1950s, developers were required by law to build additional parking whenever they built additional residential units. While this car-positive law was already being phased out in parts of Manhattan by the early 1970s, the law is still in place in many of the city's less densely populated neighborhoods. In addition to increasing the cost of new housing, the law has, over time, become increasingly misaligned with New Yorkers' priorities and the current administration's commitment to becoming Carbon Neutral by 2050.Under the original "City of Yes," housing and parking would no longer be linked, freeing developers to add new housing units citywide without adding new parking spaces. However, this proved to be one of the more contentious aspects. In response to concerns, the modified plan introduced a three-tiered system.

In the first tier, areas with extensive public transportation options (think Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn) will see the parking mandate completely eliminated. In the second tier, the parking mandate will be significantly reduced in areas with more limited but still accessible public transportation. Finally, in a third tier, the parking mandate will stay the way it is in transit deserts.

Malt Drive in the Hunters Point South master plan in Long Island City required on-site parking to be provided

Malt Drive in the Hunters Point South master plan in Long Island City required on-site parking to be provided

#5. Accessory dwelling units

Although most New Yorkers don’t have a backyard, for those who do, ADUs (accessory dwelling units) are now legal. “City of Yes” will legalize ADUs (up to 800 square feet) on one- and two-family properties across all five boroughs. In the fall of 2023, the City launched its ADU initiative with the Plus One ADU Program, which provided financing for fifteen lucky local homeowners to start their ADU projects.In September 2024, AMNY ran an editorial by the New York City Department for the Aging Commissioner and New York State AARP Director endorsing this aspect of the plan for how it could help older New Yorkers. However, residents of neighborhoods like Bayside, Queens have expressed concern that the legalization of ADUs will eat into the green space that made the areas attractive to begin with.

ADUs are still permitted in the modified plan, but with new rules in place: Ground-level and basement ADUs will not be allowed in coastal flooding zones or areas vulnerable to inland flooding. ADUs can only be one story unless they are built above parking (i.e., someone’s garage). They will not be allowed in single-family zoning districts or historic districts unless the property is near public transportation. Finally, homeowners wishing to build ADUs would be required to live on the property.

#6. Transit oriented development

In many New York City neighborhoods, zoning laws restrict not only high-rise developments but also three- to five-story developments. Over time, this has pushed many New Yorkers into the far reaches of outer boroughs and increased their commuting times to school and work. "City of Yes" proposes to lift the limit on constructing low-rise multi-dwelling units near existing transit hubs to help more New Yorkers live closer to transit centers.A March 2024 report by the Regional Plan Association went so far as to say that “[transit-oriented development] is the key to solving our region’s affordable housing crisis,” but acknowledged that outdated zoning restrictions both in New York City and the surrounding suburbs are keeping this from going forward.

The modified plan allows this, but scaled it back to three- to five-story apartment buildings within a quarter mile of the outermost LIRR and Metro-North stations, as opposed to the half mile originally proposed. Housing projects with more than 50 units will only be allowed if 20% of the units are affordable to households earning 80% of the Area Median Income. Finally, such buildings will not be allowed to rise in single-family districts.

#7. Campus housing

When most people hear “campus housing,” they think of dormitories and buildings located near the city’s top universities. But in the context of “City of Yes,” campus refers to large lots that include those owned by faith-based organizations. These lots are often home to both underutilized space and abundant development rights, but current zoning requirements keep both the organizations and developers from making the most of them. “City of Yes” seeks to make it easier to add contextual, height-sensitive buildings to these areas. This aspect was largely left unchanged in the modified plan. Designed by Morris Adjmi Architects, Mason Gray is a newly-launched rental development on the former campus of the Hebron Seventh Day Adventist Church and School

Designed by Morris Adjmi Architects, Mason Gray is a newly-launched rental development on the former campus of the Hebron Seventh Day Adventist Church and School

Forthcoming Projects

51 South 1st Street, Williamsburg

8 Stories | 6 Condo Units | Est. Completion 2027

8 Stories | 6 Condo Units | Est. Completion 2027

Architect: ARC Architecture + Design Studio | Developer: Einav Gelberg (Minrav Development)

Rendering of 51 South 1st Street (ARC Architecture + Design)

Rendering of 51 South 1st Street (ARC Architecture + Design)

Construction is underway on a new residential building near Domino Park in Williamsburg, potentially a boutique condominium. Designed by ARC Architecture + Design Studio, the low-rise structure will feature a sleek facade, broad arches, oversized windows, and terraces on every level.

Approved permits from earlier this fall indicate the building will rise six stories and include eight units spread across 15,000 square feet.

Residents will be welcomed by an attended lobby with a lush green wall. While the renderings show a rooftop terrace, it’s unclear whether this will be a shared amenity or exclusive to a penthouse. The project is expected to be completed in 2027.

Approved permits from earlier this fall indicate the building will rise six stories and include eight units spread across 15,000 square feet.

Residents will be welcomed by an attended lobby with a lush green wall. While the renderings show a rooftop terrace, it’s unclear whether this will be a shared amenity or exclusive to a penthouse. The project is expected to be completed in 2027.

2720 Church Avenue, Flatbush

17 Stories | 56 Rental Units | Est. Completion 2027

17 Stories | 56 Rental Units | Est. Completion 2027

Architect: INOA Architecture | Developer: Walid Shehadeh

Renderings of 2720 Church Avenue (INOA Architecture)

Renderings of 2720 Church Avenue (INOA Architecture)

Apartment interior renderings

Apartment interior renderings

Attended lobby

Attended lobby

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

In a low-rise section of Flatbush, the forthcoming 2720 Church Avenue is set to stand out as much for its towering height as its dramatic design: Renderings by INOA Architecture, the firm founded by Zaha Hadid and SOM protege Murat Mutlu, depict a high-rise resembling an upturned mitochondrion with winding concrete frames, floor-to-ceiling windows, and terraces on every level. Lot-line walls will remain brutally blank.

Approved permits from earlier this year show the 17-story tower will rise from a through-block site with much of the bulk situated at 119-121 Erasmus Street. It appears the one-story Associated Supermarket at 2720 Church Avenue will remain. The nearly 200' tall tower will be among the tallest in the area and will bring 56 likely rental units across its 42,000 square feet of residential floor area.

Interior renderings depict open-concept layouts with stainless steel kitchen appliances. Upper-floor apartments will have magnificent views of Brooklyn and Manhattan. Residents will arrive into an attended lobby with a green wall, and the renderings also show a fitness center with access to an outdoor terrace. Another perk will be an address just one block from the Church Avenue 2/5 trains.

Approved permits from earlier this year show the 17-story tower will rise from a through-block site with much of the bulk situated at 119-121 Erasmus Street. It appears the one-story Associated Supermarket at 2720 Church Avenue will remain. The nearly 200' tall tower will be among the tallest in the area and will bring 56 likely rental units across its 42,000 square feet of residential floor area.

Interior renderings depict open-concept layouts with stainless steel kitchen appliances. Upper-floor apartments will have magnificent views of Brooklyn and Manhattan. Residents will arrive into an attended lobby with a green wall, and the renderings also show a fitness center with access to an outdoor terrace. Another perk will be an address just one block from the Church Avenue 2/5 trains.

43-05 Crescent Street, Williamsburg

11 Stories | 39 Rental Units | Est. Completion 2027

Architect: INOA Architecture | Developer: Yong Chen of Central Realty LIC LLC

Lobby

Lobby

Fitness Center

Fitness Center

Construction is underway on a jewel-box-like, nine-story mixed-use building at 43-05 Crescent Street in Long Island City. The mid-rise will feature 39 apartments across 26,713 square feet of residential space, suggesting rentals are likely. Designed by INOA Architecture, the sleek building will showcase full-height glass walls and undulating floor slabs, evoking the style of Zaha Hadid.

The building will include a roof deck, though views may be limited due to the surrounding large-scale rental towers, such as Hayden and LINC LIC. Located at the corner of 43rd Avenue near Court Square, the site offers convenient access to the Queensboro Plaza subway station, served by the 7, N, and W trains.

The building will include a roof deck, though views may be limited due to the surrounding large-scale rental towers, such as Hayden and LINC LIC. Located at the corner of 43rd Avenue near Court Square, the site offers convenient access to the Queensboro Plaza subway station, served by the 7, N, and W trains.

757 Flatbush Avenue, Flatbush

9 Stories | 132 Condo Units | Est. Completion 2025

Architect: Morali Architecture | Developer: New Empire Corporation

New Empire Corporation is developing a large new condominium building at 757 Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn's Flatbush neighborhood. The property is a deep mid-block lot spanning nearly 40,000 square feet. Currently under construction, the development will host 132 condo units across approximately 140,000 square feet of space. Additionally, there will be 125 feet of retail frontage along Flatbush Avenue and over 20,000 square feet of retail and commercial space

Homes will range from one- and two-bedroom apartments to limited three-bedroom penthouse duplexes. All residences will feature private outdoor spaces, such as balconies and roof terraces, with views of Prospect Park and the Manhattan skyline.

A comprehensive amenity suite includes on-site parking accessed via a 30-foot driveway from Lenox Road. Other resident perks will include a fitness center, pool, sauna, hot yoga studio, resident lounges, playroom, office center, storage, bike parking, and 24/7 package delivery.

Homes will range from one- and two-bedroom apartments to limited three-bedroom penthouse duplexes. All residences will feature private outdoor spaces, such as balconies and roof terraces, with views of Prospect Park and the Manhattan skyline.

A comprehensive amenity suite includes on-site parking accessed via a 30-foot driveway from Lenox Road. Other resident perks will include a fitness center, pool, sauna, hot yoga studio, resident lounges, playroom, office center, storage, bike parking, and 24/7 package delivery.

188 East 135th Street, Mott Haven

25 Stories | 236 Rental Units | Est. Completion 2025

Architect: Archimaera / Hamish Whitefield Architects P.C.

| Developer: Regal Holding Group (Waterfront Living II LLC)

(188 East 135th Street | Credit: archimaera)

(188 East 135th Street | Credit: archimaera)

A cutting-edge apartment tower is set to rise from a cleared lot adjacent to a Metro North rail bridge on the Mott Haven's Harlem River waterfront. Recent permit activity shows an increase in scale, with plans now calling for a 25-story building featuring 236 apartments. Hamish Whitefield Architects P.C. is listed as the architects of record while a rendering by the cutting-edge design firm Archimaera shows early concepts of the tower. The image reveals a dynamic structure with structural struts, cantilevers, and expansive passive recreation spaces that will occupy a large portion of the lot.

The Dome, 234 McGuinness Boulevard / 210 Greenpoint Avenue

8 Stories | 70 Condo Units | Est. Completion 2025

Architect: JFA Architects & Engineers

| Developer: The Jay Group

In the coming months, sales will launch at The Dome, a new mixed-use condominium development at 237 McGuinness Boulevard in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Designed to pay tribute to the neighborhood’s rich Polish heritage, the building will offer studio, one, two, and three-bedroom residences featuring natural elements and high-end finishes. High-floor homes will boast breathtaking views of the Manhattan skyline, Newtown Creek, and the East River. Amenities will include a fitness center, resident lounge, game room, and rooftop lounge.

The eight-story, 70-unit building is being developed by The Jay Group and is currently under construction. In addition to the residences, the building will feature ground-floor retail space, with two sections totaling approximately 6,210 square feet. The project is ideally located near the Greenpoint Avenue subway station (G train), the Pulaski Bridge, and bus lines B24 and B62.

The eight-story, 70-unit building is being developed by The Jay Group and is currently under construction. In addition to the residences, the building will feature ground-floor retail space, with two sections totaling approximately 6,210 square feet. The project is ideally located near the Greenpoint Avenue subway station (G train), the Pulaski Bridge, and bus lines B24 and B62.

47-15 34th Avenue

11 Stories | Units: TBD | Est. Completion: TBD

Architect: Jorge Mastropietro Architects

| Developer: Ashley Young LLC and John Young Associates

(Credit: Jorge Mastropietro Architects)

(Credit: Jorge Mastropietro Architects)

A new 11-story mixed-use building is planned at 47-15 34th Avenue, at the crossroads of Astoria and Woodside, just off Northern Boulevard. Designed by Jorge Mastropietro Architects, the project will feature a modern glass facade, landscaped terraces, and ground-floor retail aimed at enhancing the surrounding cityscape.

According to the architects, the design emphasizes creating a vibrant street life, with thoughtful elements such as scaled commercial spaces, building setbacks, and strategically placed trees and street furniture. These features are intended to foster daily interactions, promote community connections, and support a safer, healthier neighborhood environment. Construction permits have yet to be filed.

In 2018, owners Ashley Young LLC and John Young Associates went to the NYC Department of City Planning to get approvals to build a 14-story building with 91 market-rate apartments, 47 affordable homes, nearly 21,000 square feet of retail and 101 parking spaces located both above and below-ground

According to the architects, the design emphasizes creating a vibrant street life, with thoughtful elements such as scaled commercial spaces, building setbacks, and strategically placed trees and street furniture. These features are intended to foster daily interactions, promote community connections, and support a safer, healthier neighborhood environment. Construction permits have yet to be filed.

In 2018, owners Ashley Young LLC and John Young Associates went to the NYC Department of City Planning to get approvals to build a 14-story building with 91 market-rate apartments, 47 affordable homes, nearly 21,000 square feet of retail and 101 parking spaces located both above and below-ground

Gansevoort Square

60 Stories | Units: Up to 600 | Est. Completion: TBD

Architect: TBD

| Developer: NYC Economic Development Corporation

Rendering of Gansevoort Square (NYCEDC)

Rendering of Gansevoort Square (NYCEDC)

In fall 2024, Mayor Adams unveiled a new vision for Gansevoort Square, a 24/7 live-work-play-cultural hub in the heart of the Meatpacking District. The 66,000-square-foot project is set to include up to 600 mixed-income housing units and a new, 11,200-square-foot public open space. It also offers potential for the expansion of the Whitney Museum of American Art, which has a Right of First Offer on the site, as well as the possibility of new High Line facilities.

Gansevoort Square is to take shape on Little West 12th Street between Washington Street and Tenth Avenue. The site is currently occupied by the Gansevoort Meat Market, but it has opted to end its lease early in cooperation with the NYCEDC and the City of New York. Gansevoort Square is still in very early stages, but early renderings show an open plaza and new retail space with the High Line above.

The proposed site is just outside the boundaries of the Gansevoort Market Historic District. However, Village Preservation has expressed concerns about the building’s possible height of 60 stories high, noting that this would be more than two and a half times the size of the nearby Standard Hotel, which is now the tallest building in the Meatpacking District.

Gansevoort Square is to take shape on Little West 12th Street between Washington Street and Tenth Avenue. The site is currently occupied by the Gansevoort Meat Market, but it has opted to end its lease early in cooperation with the NYCEDC and the City of New York. Gansevoort Square is still in very early stages, but early renderings show an open plaza and new retail space with the High Line above.

The proposed site is just outside the boundaries of the Gansevoort Market Historic District. However, Village Preservation has expressed concerns about the building’s possible height of 60 stories high, noting that this would be more than two and a half times the size of the nearby Standard Hotel, which is now the tallest building in the Meatpacking District.

Paragon, 45-40 Vernon Boulevard

23 Stories | Units: 226 | Est. Completion: 2026

Architect: Archimaera

| Developer: ZD Jasper

Renderings of Paragon (ZD Jasper)

Renderings of Paragon (ZD Jasper)

Demolition work is underway for Paragon, a new mixed-use building on the rise in Long Island City. Renderings show that the industrial structure once known as the Paragon Paint Building will be incorporated into a new tower. Renderings depict a new tower with massive casement windows rising from the historic structure.

The finished product will rise 23 stories high and offer 226 housing units (likely rentals) on top of lower-level commercial space. Developer ZD Jasper lists MAWD as the interior designer. Information is not yet available on residential amenities, but the project will include a landscaped plaza extending to 46th Avenue. Another perk will be its address near Gantry Plaza State Park, popular Long Island City restaurants, multiple subway lines, and the Long Island City ferry terminal.

The finished product will rise 23 stories high and offer 226 housing units (likely rentals) on top of lower-level commercial space. Developer ZD Jasper lists MAWD as the interior designer. Information is not yet available on residential amenities, but the project will include a landscaped plaza extending to 46th Avenue. Another perk will be its address near Gantry Plaza State Park, popular Long Island City restaurants, multiple subway lines, and the Long Island City ferry terminal.

One45, 124 West 145th Street, Harlem

34 Stories | 968 Rental Units | Est. Completion 2029

Architect: SHoP Architects

| Developer: Bruce Teitelbaum

One45

One45

Set for completion by 2029, the One45 project, proposed by developer Bruce Teitelbaum, envisions a transformative 34-story mixed-use complex at 124 West 145th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard in Harlem. The development includes 968 residential units, with 300 affordable apartments and 125 supportive housing units, alongside community facilities and retail space. Designed to promote sustainable urban living, the project notably omits parking, leveraging its prime location near a subway station.

This updated proposal, now advancing through the city's land use review process, follows earlier plans that were shelved in 2022 due to political opposition. With the extension of the state’s 421a tax incentive and backing from Councilmember Yusef Salaam, the project has regained momentum. Teitelbaum has revised the design to include greater affordability and removed "poor doors" to align with state regulations.

This updated proposal, now advancing through the city's land use review process, follows earlier plans that were shelved in 2022 due to political opposition. With the extension of the state’s 421a tax incentive and backing from Councilmember Yusef Salaam, the project has regained momentum. Teitelbaum has revised the design to include greater affordability and removed "poor doors" to align with state regulations.

21 Garden Street, Bushwick

8 Stories | 50 Rental Units | Est. Completion 2025

Architect: DXA Studio

| Developer: Travis Stabler's Rivington Company

Designed by DXA Studio and developed by Travis Stabler's Rivington Company, 21 Garden Street is an eight-story rental building taking shape in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Construction topped out earlier this year, with leasing expected to begin in 2025.

The building’s standout feature is a 22-foot cantilever overhang at the penthouse levels, which was made possible by acquiring air rights from adjacent lots. The façade will feature a light limestone-colored fiber cement rainscreen, creating a monolithic masonry appearance, while angled south-facing windows and brass-toned frames enhance natural light and add visual depth to the industrial streetscape.

The project plans to designate 11 units for households earning up to 80% of the area median income (AMI). These affordable units will include eight one-bedroom and three two-bedroom apartments and will seek benefits under the 421-a tax exemption program.

The building’s standout feature is a 22-foot cantilever overhang at the penthouse levels, which was made possible by acquiring air rights from adjacent lots. The façade will feature a light limestone-colored fiber cement rainscreen, creating a monolithic masonry appearance, while angled south-facing windows and brass-toned frames enhance natural light and add visual depth to the industrial streetscape.

The project plans to designate 11 units for households earning up to 80% of the area median income (AMI). These affordable units will include eight one-bedroom and three two-bedroom apartments and will seek benefits under the 421-a tax exemption program.

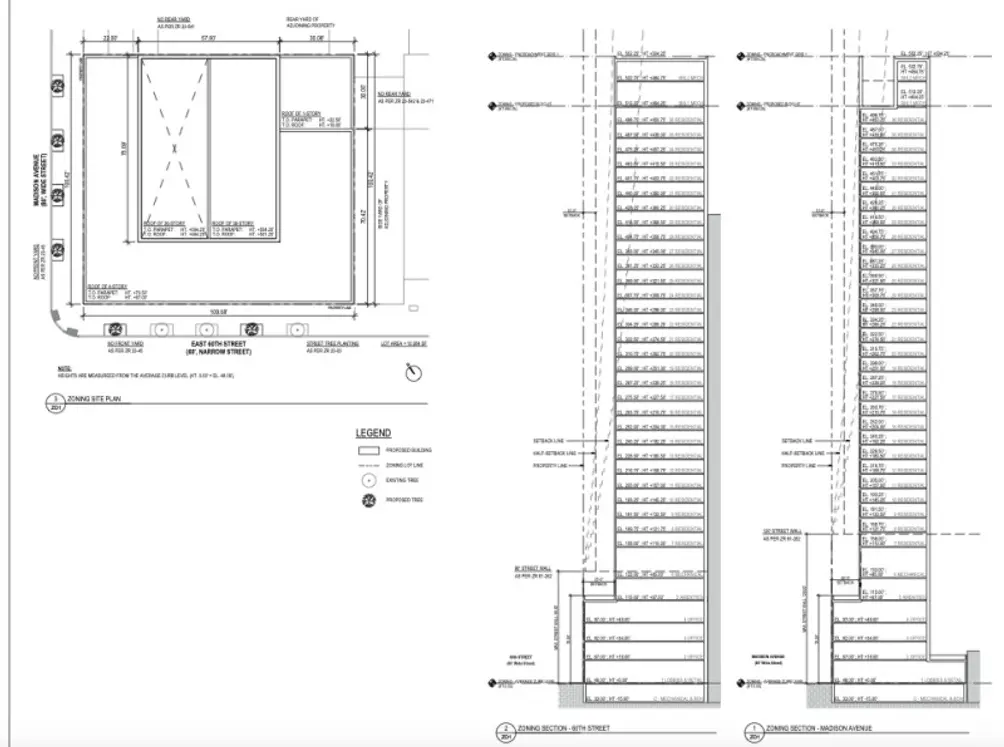

655 Madison Avenue, Upper East Side

37 Stories | 62 Condo Units | Est. Completion TBD

Architect: Beyer Blinder Belle | Developer: Extell Development Company Company

Zoning diagrams via NYC DOB

Zoning diagrams via NYC DOB

Gary Barnett's Extell Development Company recently filed plans to build 37-story mixed-use condo tower at 655 Madison Avenue at the southeast corner of East 60th Street. Located at the cusp of Midtown's Plaza District and the Upper East Side, mid- and high-floor homeswill enjoy coveted Central Park and Manhattan skyline views.

Beyer Blinder Belle is listed as the architect of record, a firm adept in traditional high-end design. Drawings show a slender tower deeply setback from a commercial podium. The project will span approximately 193,000 square feet and include a combination of retail, hotel, office, and residential space. The first six floors will house the commercial and hotel components, while the upper levels will feature residential units with high ceilings. The split between hotel rooms and permanent residences remains unclear from the filings.

To make way for the new 500-foot tall tower, Extell is demolishing the existing 24-story office building on the site, a process initiated earlier by the property’s previous owner, Williams Equities. Extell acquired the property in October 2024 for $160 million from a joint venture between Williams Equities and Jamestown.

Beyer Blinder Belle is listed as the architect of record, a firm adept in traditional high-end design. Drawings show a slender tower deeply setback from a commercial podium. The project will span approximately 193,000 square feet and include a combination of retail, hotel, office, and residential space. The first six floors will house the commercial and hotel components, while the upper levels will feature residential units with high ceilings. The split between hotel rooms and permanent residences remains unclear from the filings.

To make way for the new 500-foot tall tower, Extell is demolishing the existing 24-story office building on the site, a process initiated earlier by the property’s previous owner, Williams Equities. Extell acquired the property in October 2024 for $160 million from a joint venture between Williams Equities and Jamestown.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Contributing Writer

Cait Etherington

Cait Etherington has over twenty years of experience working as a journalist and communications consultant. Her articles and reviews have been published in newspapers and magazines across the United States and internationally. An experienced financial writer, Cait is committed to exposing the human side of stories about contemporary business, banking and workplace relations. She also enjoys writing about trends, lifestyles and real estate in New York City where she lives with her family in a cozy apartment on the twentieth floor of a Manhattan high rise.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.