Steinway Hall stands newly restored alongside the rising supertall 111 West 57th Street. Images via JDS Development and Property Markets Group

Steinway Hall stands newly restored alongside the rising supertall 111 West 57th Street. Images via JDS Development and Property Markets Group

The supertall tower in the works at 111 West 57th Street is proof that historic New York can sit comfortably beside extreme heights. Slated to top out at 1,421 feet, JDS and Property Markets Group's skyscraper will ultimately reign among the tallest towers in the city and as the most slender skyscraper in the world.

The supertall tower stands connected and adjacent to the original landmarked Steinway Hall designed in 1925 by Warren & Wetmore (architects of Grand Central Terminal), where Steinway & Sons housed its iconic collection of pianos. During development, the team accounted for the prominent 10-story building by restoring its façade to its former limestone glory and incorporating it as the arrival point of the new address.

In this article:

Model and photo credit: Radii

Model and photo credit: Radii

Soon to become an integral part of 111 West 57th Street, the old Steinway Hall carries its own rich history intertwined with the emergence and growth of Steinway & Sons to the most prominent name in the piano business. Like many buildings in New York City, the edifice is the product of the ambition and success of one talented family – in this case, a talented family of piano manufacturers and sellers.

The history of Steinway Hall begins with Heinrich E. Steinweg, Sr., the owner of a piano and instrument shop in Germany. After his son, Charles, immigrated to New York in 1849 and confirmed the rich potential within the nation’s piano market, Steinweg officially founded his piano manufacturing firm Steinway & Sons in 1853. (The family legally changed its surname in 1864.)

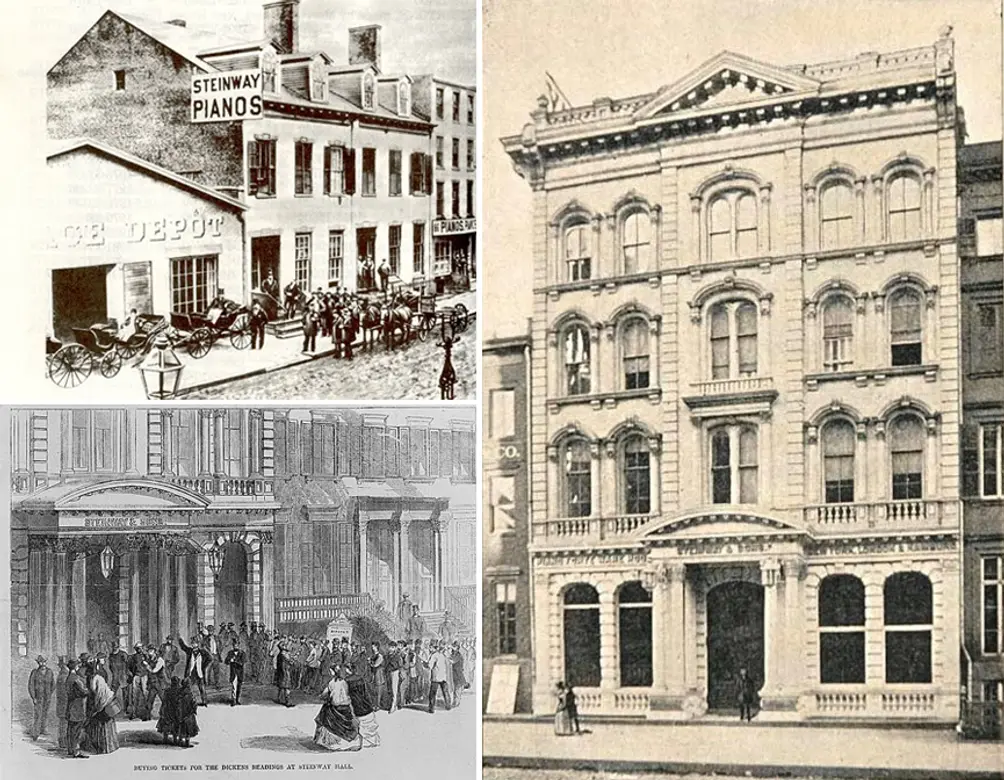

Upper left photo shows Steinway's Tribeca space at 82-88 Walker Street; Lower-left and right image shows the first Steinway Hall at 71-73 East 14th Street near Union Square

Upper left photo shows Steinway's Tribeca space at 82-88 Walker Street; Lower-left and right image shows the first Steinway Hall at 71-73 East 14th Street near Union Square

The firm was first housed in a loft at 85 Varick Street, and then migrated to larger quarters in several adjacent buildings at 82-88 Walker Street the next year. Henry and his sons Charles, Henry Jr., William, and Albert handled the firm’s business and growth.

To meet this growth, Steinway opened a showroom, piano depository, and offices at 71-73 East 14th Street in 1864, and opened Steinway Hall as an addition to this building’s rear two years later.

Toward the end of the decade, the family’s grand plans included the construction of a mechanized pianoforte manufactory on Park Avenue and 53rd Street (where the Seagram building stands today), one of the largest of its kind in the world. Here, with a workforce consisting of 350 employees, the firm increased production growth from 500 to 1,800 pianos per year.

The firm's pianoforte manufactory on Park Avenue (where the Seagram Building now stands)was completed in 1860. Image via JDS/Property Markets Group.

The firm's pianoforte manufactory on Park Avenue (where the Seagram Building now stands)was completed in 1860. Image via JDS/Property Markets Group.

With the deaths of both Charles and Henry Jr. in 1865, the piano patriarch’s other son Theodore (who had remained in the Germany piano business) moved to New York to join his family. He served as the technical director, while William served as financial/business director and handled marketing and promotion. Together, the two elevated Steinway & Sons to international prominence.

via http://www.boweryboyshistory.com

via http://www.boweryboyshistory.com

In 1870, unable to expand in the Union Square area any further, the firm began acquiring what would become 400 acres of property in Long Island City. During this decade, Steinway developed a company town, complete with housing and a complex that included a lumberyard, sawmill, foundry, piano factory, and piano case works. The existing Park Avenue locale became the firm’s finishing manufactory.

In 1875, the firm expanded across the Atlantic, opening a showroom and Steinway Hall in London, and a branch factory and showroom in Hamberg five years later.

With the 1891 debut of Carnegie Hall on West 57th Street, the area just south of Central Park solidified its presence as one of the nation’s leading cultural and classical music centers. As piano companies relocated uptown to capitalize on this movement, Steinway & Sons looked to do the same.

Fast forward to 1916, when the firm announced a new ten-story building on 57th Street directly across the street from Carnegie Hall, and to 1923, when it officially acquired the site. Steinway commissioned architects Warren & Wetmore to complete their vision, a firm whose resume includes no less than the design of Grand Central Terminal.

The resulting 1925 neo-Classical tower rose on an L-shaped plot, with its front portion finished in Indiana limestone and culminating in a set-back, four-story colonnaded tower, and a central campanile-like tower with a steep pyramidal roof and large lantern. Its base flaunted a sculptural group designed by Leo Lentelli and a frieze with medallion portraits of distinguished classical composer-pianists.

The building’s grand style, materials, setbacks, towers, and decorative elements each served to make physical the firm’s presence as a leader in the arts community. Contributing to the firm’s great success was a combination of technical developments, efficient and high-quality production, shrewd business measures, and strategic promotion through artist endorsements and advertisement. Over the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Steinway family acquired over 100 technical patents (ultimately 127) and served to contribute to the development behind the modern piano today.

Photos via Landmarks Preservation Commission

Photos via Landmarks Preservation Commission

Earning recognition early on for the superior craftsmanship and design of its pianos, Steinway went on to garner numerous awards to quantify a lasting legacy. Among them are 35 first prizes at the American industrial fairs (1855-62); first prize at the International Exhibition, London (1862); gold medals for its grand, square, and upright models at the Exposition Universalle, Paris (1867); and the top piano award at the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia (1876).

Within the building at 109 West 57th Street itself, Steinway & Sons occupied the lower five levels. The basement was used for storage and shipping, and included an area designed for artists to test concert grand pianos. The first story held a Reception Room and salesrooms, the second included additional salesrooms, the third boasted Steinway Hall itself – the recital hall seating 240 persons – as well as executive offices, and the fourth and fifth stories offered insulated rental music studios. Above, the remainder of the building served to house rental offices, which have included the Oratorio and Philharmonic Societies of New York, Columbia Artists Management, Inc., and The Manhattan Life Insurance Company.

For the remainder of the twentieth century, Steinway Hall served as the single sales location for the firm’s renowned pianos in New York City. Countless musicians and composers passed through its halls, which included an inventory of over 300 pianos valued at over $15 million. In 2001, the structure achieved its landmark status, with its interior rotunda and Reception Room and Hallway following suit in 2013.

The building’s ongoing piano legacy lasted until 2013, when Steinway sold its leasehold interest to JDS Development Group, moving to 1133 Sixth Avenue in 2016.

With the 2013 sales came plans for the adjacent 111 West 57th Street, rising on the site today, with the old Steinway Hall building’s air rights accommodating the 82-story tower. SHoP Architects designed an elegant and traditional exterior, featuring a curtain wall of terra cotta, glass, and bronze filigree.

Inside, 60 full-floor and duplex condos designed by Studio Sofield are to be finished in marble, dark woods, and bronze, uniting voluminous interiors with its classically-inspired exterior. Oversized windows and 12-foot ceiling heights will serve to provide views of Central Park and the city beyond.

Not just for show, Steinway Hall’s newly refinished exterior will house the arrival for the supertall building, offering a private porte cochere. The development is due for completion next year.

111 West 57th Street and the Steinway Building as of late May 2018 (Photo credit: Ondel Hylton for CityRealty)

111 West 57th Street and the Steinway Building as of late May 2018 (Photo credit: Ondel Hylton for CityRealty)

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Contributing Writer

Katy Cornell

Katy Cornell is a Long Island native with a passion for writing about real estate in the big city. She recently graduated from the University of Virginia with a BA in English and is a frequent contributor to CityRealty's Market Insight and NYC real estate blog 6sqft.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.