West Village by JS Chauma

West Village by JS Chauma

The iconic grid shape of Manhattan’s streets did not happen by accident. Sensing that the city would expand, the City Council decided that they would need a plan for the future. By March of 1807, the state legislature appointed a three member commission consisting of a well-known statesman, a lawyer, and the state surveyor. Those men created what would become the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, an eight-foot map with an accompanying 54-page pamphlet that laid out development for the centuries to come. But if you have ventured below West 14th Street, you would see a cityscape starkly different than the orderly north-south avenues and east-west streets. The streets are often narrow, and many feature odd curves. And unlike most of the City above Houston, the streets are named not numbered. This is because the section we now refer to as Greenwich Village far predates the rest of the city by a considerable amount of time.

In this article:

As early the sixteenth century, Native Americans referred to the area adjacent to the Hudson River as ‘Sapokanikan’, their nomenclature for tobacco field. This marshy land was home to a small feeder stream that ran into the Hudson River known as Mannete that had a healthy population of Brook trout. Perhaps it was this food source that had attracted the Algonquin. This land, near present-day Gansevoort Street, was turned into pasture by Dutch settlers. There is record a settler, who worked for the Dutch East India Trading company and would later become Governor of the hamlet, farming 200 acres of tobacco as early as the 1630s. The Dutch also brought Freed African slaves with them that also worked sections of this fertile land. Eventually this region became known as Noortwyck, or “North District”. The English would go to war with the Dutch, taking over New Netherland in 1664. The settlement morphed into a country hamlet, officially called Greenwich in Common Council records from 1713, although the earliest known reference to that name came from a will written in 1696.

Greenwich Village got through the Revolutionary war relatively unscathed, with no major skirmishes taking place nearby. The stream previously referred to as Mannete came to be known as the Minetta Brook, and later would be covered with wooden boards so people could walk over it. In April of 1797, the Common Council of New York purchased the fields to the east of the Brook for a new potter's field, a parcel of approximately eight acres. Starting in 1799, disease began to ravage the rest of New York City. In 1799, 1803, 1805, and 1821, both Yellow Fever and Cholera laid siege to the city proper. As it was isolated from the rest of the city, many fled to Greenwich to escape these plagues and set up temporary housing. An outbreak in 1822 spurred many whom had planned on leaving to set up a permanent residence. The population increased by 400 percent between 1825 and 1840, giving birth to new marketplaces and businesses. Row houses started springing up, mostly in the Federal style architecture that was popular at the time.

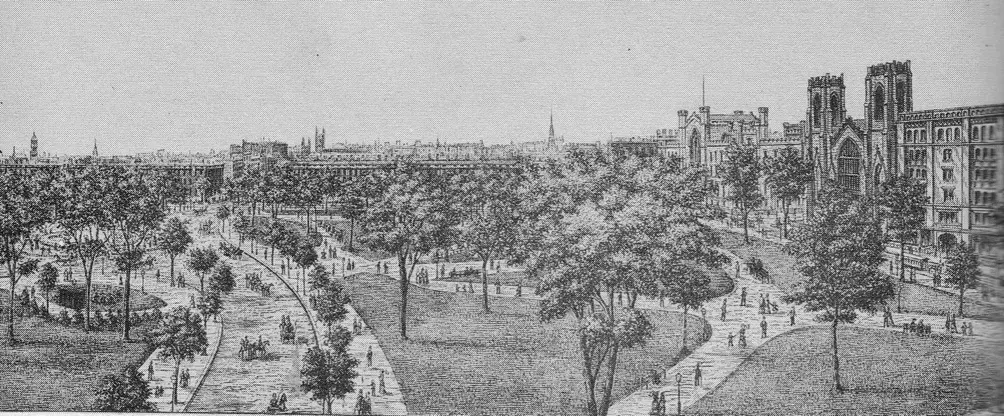

Washington Square in the 1880s

Washington Square in the 1880s

The potters’ field would provide the final resting place for an estimated 20,000 people, most of them victims of the outbreaks, before it was closed in 1825. In 1826 it was leveled and converted into the Washington Military Parade Ground, a space for the volunteer militia companies that were tasked with protecting the country could train. The streets surrounding the square became one of the most desirable residential areas; with red brick townhouses in the Greek Revival style accommodated the wealthy elite. The Parade Ground was reworked again in 1849 and 1850, creating more in line with what we know today as Washington Square Park. Additional paths were constructed, and a new fence was erected around the perimeter. In the early 1870s it came under control of the newly minted New York City Department of Parks, who redesigned it with curved secondary paths replacing previous straight ones. But the most recognizable feature of the park wasn’t erected until 1892. To replace an exceedingly popular temporary wood and plaster arch that had been created to commemorate the centenary of George Washington’s inauguration as President, the iconic marble arch was built in the style of the Arc de Triumph.

Waves of immigrants descended upon Greenwich Village in the latter part of the 19th century. Pilgrims from Italy, Ireland, Germany, and France came to work in the warehouses and coal and lumber yards near the Hudson River. They also found employment in the manufacturing lofts in the southeast corner of the neighborhood. They all brought with them their cultures, religions, and their traditions. At the same time, there was a rise in Bohemianism. This influx of outside influences began to change the character of the neighborhood. This caused the departure of many of the well to do residents, sending them fleeing to more fashionable areas around Fifth Avenue and the recently constructed Central Park. Commercialization began to descend upon the tiny hamlet. Large factories, such as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory that was home to one of the worst workplace tragedies in history, began to spring up. Many residential buildings were converted into low-income housing or multiple-family dwellings, or were destroyed in favor of large apartment buildings.

This influx of cultures made the Village exceptionally ethnically diverse. The Bohemian movement had entrenched itself fairly well, with the now-low rents being welcomed by starving artists. The neighborhood developed a reputation as a haven for the unconventional; with art galleries showcasing innovative modern works and experimental theater companies. As this reputation spread, it attracted tourists and artists alike from all corners of the globe. The lure of the Speakeasies drew crowds from throughout the city during Prohibition. Much of the infrastructure that had fallen into disrepair was being revitalized; in the mid-1920s luxury apartments were constructed at the northern edge of Washington Square. By the 1950s, the village had become the cultural center of the Beat Movement. Bleecker Street played host to many small theaters, Eighth Avenue was littered with art galleries, and MacDougal Street had coffee shops and cafes where many writers would go to practice their craft.

White Horse Tavern

White Horse Tavern

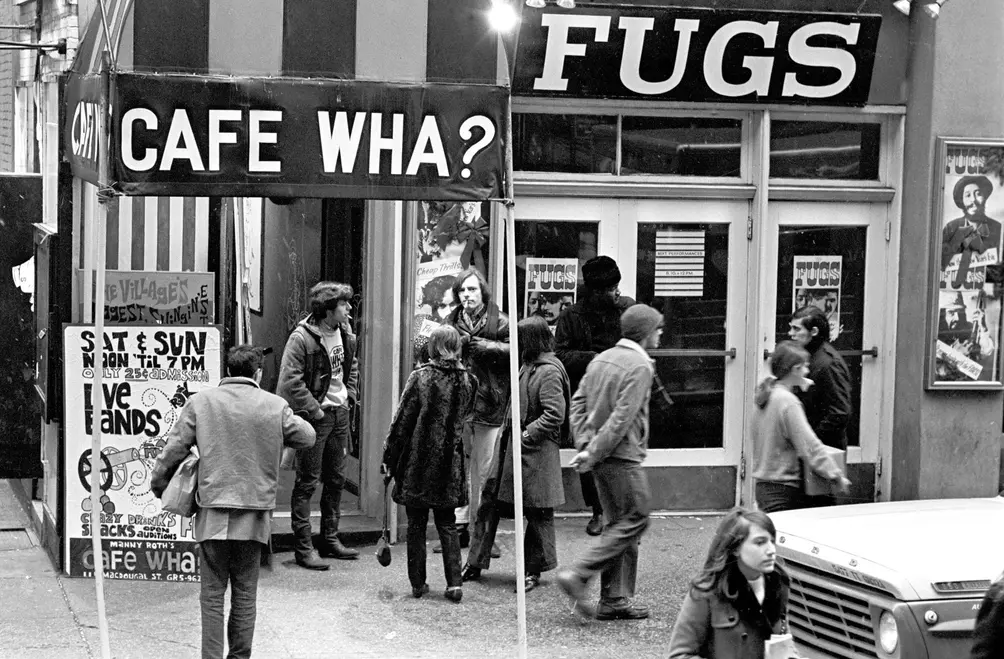

Cafe Wha?

Cafe Wha?

MacDougal Street would prove to be an important gathering place, and venue, for cultural icons from Jack Kerouac to Richard Pryor. Opened in 1880 as a longshoremen's bar, the Whitehorse Tavern became a hangout for many writers. "JACK GO HOME!” was scrawled on the wall, as Kerouac would often imbibe too much and be bounced from the establishment. “Basket Houses," venues where unpaid artists would perform and pass around a basket at the end, starting springing up in the late fifties, attracting the many talented entertainers that would sing for their supper. The Gaslight Café opened in 1958 with poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso as headliners, though later folk music would become the main attraction. It is believed that this was the first venue that Bob Dylan ever performed in. Café Wha? opened the following year, and attracted a litany of musicians and comedians. Musical acts like Kool and the Gang, The Velvet Underground, Cat Mother & the All Night Newsboys, Peter, Paul & Mary, Jimi Hendrix, and Bruce Springsteen all got their start here. Comedians such as Woody Allen, Lenny Bruce, Joan Rivers, Bill Cosby, and Richard Pryor would keep patrons laughing well into the night.

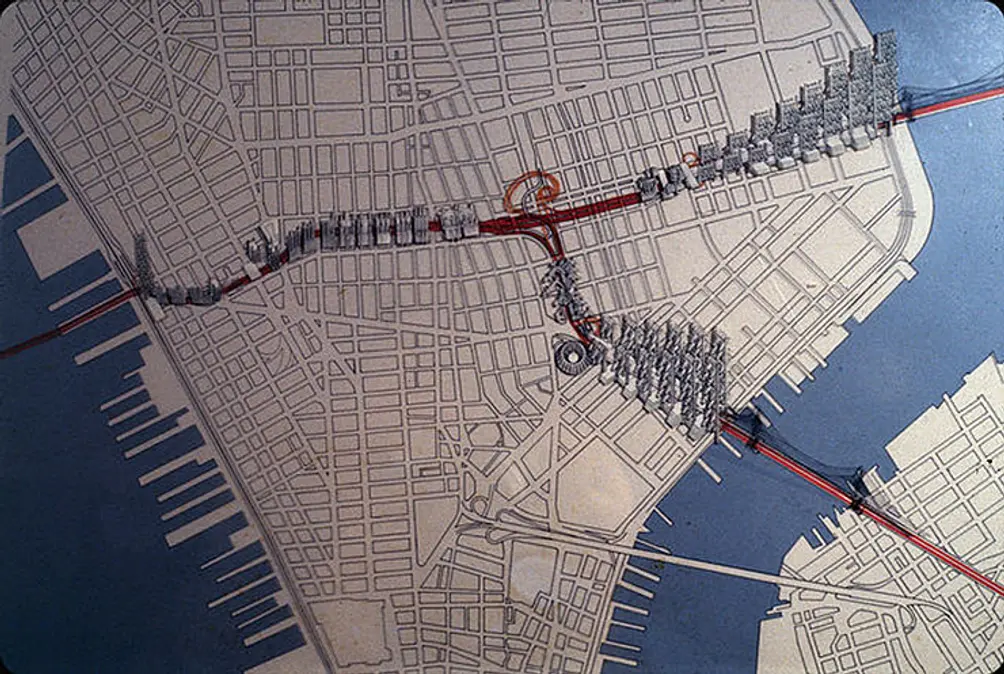

Lower Manhattan Expressway proposed by Robert Moses

Lower Manhattan Expressway proposed by Robert Moses

Robert Moses, one of the most polarizing urban planners of all time, rose to power with the election of Governor Smith. Preferring a network of highways to public transportation, he had a different vision for Greenwich Village. He had planned to place a freeway that he referred to as the Lower Manhattan Expressway through the center of Washington Square Park. A number of the Village’s residents were unhappy with the plan, the least of which was Jane Jacobs. Jane, despite lacking a college degree, was a renowned journalist that had fallen in love with the character of old cities when she was sent to cover a development in Philadelphia. She led the fight to stop Moses’ plans, chairing the Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway. The Committee eventually succeeded in blocking the project, and the city closed Washington Square Park to traffic on June 25, 1958. She continued to fight the project tooth and nail until it was finally abandoned for good in 1968 after a protest ending in a near riot.

That wouldn’t be the only tumult the Village would host in that era. Because of the hamlet’s counter-culture reputation and open mindset, it had attracted a large population of homosexuals. While the community didn’t seem to mind, many of the local bars and clubs received plenty of harassment from law enforcement officials. In the wee morning hours of June 28, 1969, the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street was raided by police. The police lost control of the situation, and many of the bar’s patrons fought back. A riot erupted, and went on for hours, rekindling the following evening and again several days later. This lead to a series of spontaneous protests that would be known as the Stonewall Riots, perhaps one of the most important events in the fight for LGBT rights in this country. A scant six months later, there were two gay rights advocacy groups within the city. And on the two-year anniversary of the Stonewall incident, the first Gay Pride marches took place in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

The Stonewall Riots

The Stonewall Riots

The Stonewall Inn today

The Stonewall Inn today

It was the Village’s gay population that was the hardest hit in the AIDS epidemic of the 80s and 90s. And at the center of it all was Saint Vincent’s Hospital. It was home to the first, and the largest, AIDS ward on the East Coast. Regarded by many as "Ground Zero" for the outbreak, untold thousands were treated in the hospital, and untold thousands died. The hospital was also adjacent to The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, known simply to those in the community as "The Center," which is where many of the first AIDS advocacy and support groups, such as ACT UP, first organized. Though iconic, Saint Vincent’s Hospital went bankrupt in April of 2010, and the former hospital campus was sold to a property management firm. As part of the deal to convert the complex into luxury condominiums, the developers must build new public open space as part of its project. The triangle of land bordered by 7th Avenue, 12th Street, and Greenwich Avenue will house an AIDS memorial park in the not-too-distant future. This park will provide both greenspace, and will pay tribute to the historic significance of the site.

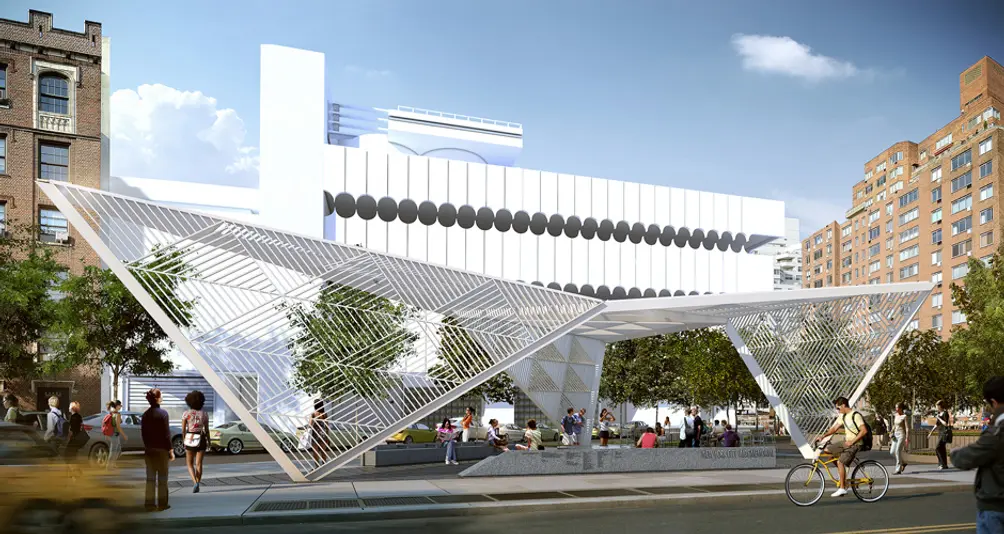

Aids Memorial Park by studio a+i

Aids Memorial Park by studio a+i

Much like Robert Moses did 60 years ago, New York University has a different plan for the Village’s layout. A fixture since its charter in 1831, NYU has recently expressed an interest in expanding their grounds. Because they lack a large, central campus they plan to expand over the next 20 years to the two large blocks to the southeast of Washington Square Park, as well as in a one block radius for as much as two million square feet of development, much to the ire of many residents. When asked, Andrew Berman of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation had this to say “NYU’s massive expansion plan is bad for the Village, bad for New York City, and bad for the university itself. It’s another step towards NYU trying to turn the Village into a company town, and a vital urban neighborhood into its own campus. [… ] The Village will be losing open space, light, air, and a diversity of character; the City and the university will lose an opportunity to expand in a more thoughtful way that could help spur useful economic diversification in other part of the city’s, instead of the overkill it will produce in the Village.”

It would seem that throughout history, the only constant is change- though the Village hasn’t transformed much in comparison to the rest of the New York City Skyline. Perhaps the ongoing battle between Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation and New York University will evoke shades of the Jacobs/Moses clash in the previous century. Only time will tell what the future of this storied Hamlet will be; but if it were up to many of the residents it would stay much the same as it is now.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.