872 Park Place, #TH (Corcoran Group)

872 Park Place, #TH (Corcoran Group)

In some cities, people talk about the weather because it is the one topic to which everyone can relate. In New York City, people talk about real estate. Real estate, perhaps more than any other factor, defines one’s experience of the city. It is also a common and chronic source of complaint. From dysfunctional and nonexistent kitchen facilities to cranky co-op boards to bizarre local bylaws, New York real estate is its own entity. This article explores the top ten NYC real estate quirks.

In this article:

Eat-in kitchens are a luxury

If you’re new to New York City, and someone offers to show you an apartment with an eat-in kitchen (or EIK, as some listings call it), you’re in luck. In most cities, no one talks about EIKs because it is generally assumed that one’s kitchen will be large enough to eat in. In New York City, EIKs, even those that only have enough room for a small table with two stools, are surprisingly rare.

328 West 96th Street, #1A1B

$1,050,000

Riverside Dr./West End Ave. | Cooperative | 2 Bedrooms, 2 Baths | 1,150 ft2

328 West 96th Street, #1A1B (Corcoran Group)

Kitchens are an afterthought

While a few New Yorkers are lucky enough to rent or buy an apartment with an EIK, most settle for a unit with either a galley kitchen or an open kitchen/living space (this is a kitchen that is actually in one’s living room). There are also New Yorkers who don’t have a proper kitchen at all.In contrast to many other North American jurisdictions, in New York City, apartments can be rented and sold without a legal kitchen and simply a kitchenette. By definition, kitchens must be eighty square feet or more, feature fire-retardant walls, have a gas or electricity source, and a window that opens onto the street or air shaft. A kitchenette is any kitchen facility that measures less than eighty square feet or fails to meet these criteria.

336 East 77th Street, #11 (Nest Seekers LLC)

Rockefeller Apartments, #2H (Brown Harris Stevens Residential Sales LLC)

NYC bathtubs are sometimes found in kitchens

While a bathtub in the kitchen is becoming an increasingly rare find in New York City, at one point, bathtubs were a common feature of kitchens. To this day, it is still possible to find kitchen-bathtubs — generally in unrenovated, pre-war walk-ups that were constructed before the dawn of indoor plumbing. Unit #13 at 328 E 6th Street.

Unit #13 at 328 E 6th Street.

Flexed doesn’t mean larger

When most people hear the word “flexed,” they think of something large and robust. In the world of New York City real estate, “flexed” generally refers to something smaller than it sounds. For example, a flexed one-bedroom is a studio that has had a wall — legally or illegally erected — to create a separate bedroom. A flexed two-bedroom is generally a one-bedroom unit that has been converted into a two-bedroom unit and so on. While some flexed apartments are highly functional, others are small, dark, and, worse yet, illegal. As a result, when renting or buying a flexed unit, first ensure that the unit is in compliance (many flexed units fail to meet local building and fire codes).The Peter James, #3D (Corcoran Group)

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Security and brokerage fees can exceed mortgage down payments in other U.S. cities

Although a host of new rental regulations rolled out in 2019 means that owners and management companies can no longer demand that tenants pay several months’ security upfront, renting an apartment in New York City remains a costly endeavor. If you want to rent a two-bedroom apartment, which will likely cost at least $3,500 monthly (more in many areas of Manhattan), your first month’s rent and security will be at least $7,000. But you will likely also be expected to pay a brokerage fee, which generally ranges from 12 to 15 percent of the first year’s rent. On a $3,500 unit, this means coming up with an additional $5,040 to $6,300 per year, or as much as $13,300 in total to simply rent an apartment. In many U.S. cities, especially those with depressed economies like Detroit, $13,000 is still a viable down payment to purchase an entire house.Two identical apartments near each other can be rented or sold at vastly different rates

From time to time, you hear stories about people living in a three-bedroom apartment in Manhattan for just a few hundred dollars a month. While these stories are rare, thanks to rent control, these stories aren’t fictional. To date, there are still more than 25,000 rent-controlled apartments in New York City, and most do carry rents that reflect 1975, not 2025 rates.If you’re eager to find one of these mythical units, however, don’t get your hopes up. Rent controlled apartments exist in private dwellings, generally constructed before 1947, and they must have been continuously occupied by their tenants (or an immediate family member) since July 1, 1971. But you may still find a rent-stabilized unit. In fact, many of the cites’ newest buildings contain rent-stabilized units. While they aren’t as affordable as rent-controlled units and eligibility is based on the area median income, they continue to offer a reasonably affordable housing option to lower and middle-income New Yorkers.

On the buying side of the market, disparities also exist. Thanks to the Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) program, apartments that may be worth more than a million on the regular market are sometimes available for just a fraction of the price. While HDFC units come with many benefits, they also come with a few notable catches. First, to qualify, you

and your family will need to meet specific income restrictions (many New Yorkers, even middle-class New Yorkers, make too much to qualify for these affordable units). Second, HDFC units are located in co-op buildings, and when they do go on sale, financing is often restricted (e.g., many HDFC sales only permit 20 or 40 percent financing). These restrictions can make these bargain units difficult for the average buyer to purchase.

257 West 86th Street, #10D (Sothebys International Realty)

Cooperative boards can’t legally discriminate, but they can reject you

New York City co-op boards have a reputation for being quirky, difficult, and even discriminatory, and the reputation is generally well deserved. For every friendly and collaborative co-op board, many others may appear to operate according to their own rule of law. To clarify, it is illegal for a co-op board to discriminate against an applicant based on their age, race, religion, sexual orientation, or marital status.Still, co-op boards do have broad latitude when assessing potential applicants. For example, while a co-op board can’t technically reject an applicant because they are not a U.S. citizen, they can conclude that a foreign buyer poses a higher than average financial risk, thereby making them less preferable than an American applicant. And co-op boards aren’t just concerned with applicant’s financial backgrounds. If everyone in the building agrees, there is nothing to stop a co-op board from banning applicants with cats, dogs, or children or applicants who list their professions as tap dancer or drummer.

You can legally raise chickens, rabbits, and bees in New York City

If you’re an urban farmer, New York City isn’t the worst place to live. Chickens (that is, hens, but not roosters) are legal. So, you’re free to raise hens in your backyard (if you have one), but if you’re thinking about hiding a rooster or goose or any other type of fowl, think again. Fines for illegal fowl range from $200 to $2000 dollars. If you’re not keen on hens, you can also raise rabbits in your backyard. Finally, since 2010, beehives, which were once strictly forbidden, have also become legal. Many buildings, including the United Nations building in Midtown and the Javits Center on the Far West Side, have their own beehives. This townhouse with accompanying carriage has a courtyard with urban farming potential (Compass)

This townhouse with accompanying carriage has a courtyard with urban farming potential (Compass)

The lights are always on, but no one lives in mechanical voids

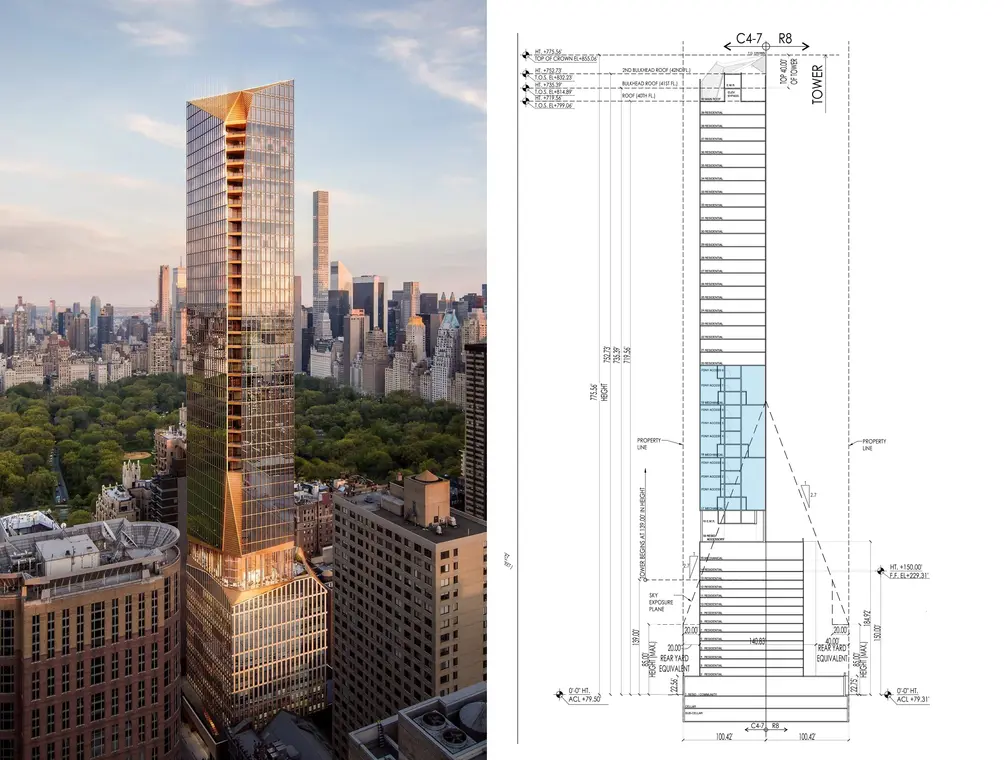

If you stand in the middle of Central Park at night, it’s hard not to notice the towers soaring about the skyline at the south end of the park. You’ll also likely notice that these extremely tall buildings are usually dark, except a few bands of light in the middle. These illuminated spaces aren’t home to residents who like to keep their lights on all night long. In fact, these illuminated spaces are where these ultra-tall buildings house their mechanical voids.Technically, mechanical voids are supposed to house essential mechanical equipment, but many of the city’s newest buildings were constructed with mostly empty multi-floor mechanical voids. While it is no longer legal, prior to 2019, some developers were exploiting a loophole in the local building code that permitted them to legally use mechanical voids to build far above local height restrictions.

The re-approved 44-50 West 66th Street (Extell Development)

The re-approved 44-50 West 66th Street (Extell Development)

Over 60,000 New Yorkers are homeless, and close to 250,000 local homes sit empty

In addition to all the space being occupied by excessively large mechanical voids, an estimated 250,000 homes in New York City sit empty at any given time. Most empty homes are vacant for a legitimate reason. For example, the home is being renovated, awaiting a new occupant, or functions legally as a pied-a-terre. Among the city’s many vacant homes, there is also a small percentage of zombie homes. These are homes that are vacant and usually deteriorating. To tackle the zombie home problem, in 2016, New York State introduced the Zombie Property and Foreclosure Prevention Act or “ZombieLaw.” Sadly, while many New York homes are empty, a report from the Coalition for the Homeless found that homelessness in New York City has reached the highest level since the Great Depression, and that it is estimated that over 350,000 New Yorkers were without homes in December 2024.

872 Park Place, #TH (Corcoran Group)

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Contributing Writer

Cait Etherington

Cait Etherington has over twenty years of experience working as a journalist and communications consultant. Her articles and reviews have been published in newspapers and magazines across the United States and internationally. An experienced financial writer, Cait is committed to exposing the human side of stories about contemporary business, banking and workplace relations. She also enjoys writing about trends, lifestyles and real estate in New York City where she lives with her family in a cozy apartment on the twentieth floor of a Manhattan high rise.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.