Cary Tamarkin is the founder and president of Tamarkin Co., an architecture and real estate development company established in 1994 and based in New York City. He worked as an architect exclusively for many years before deciding to go into development. As it turned out, he was able to combine his passion for both architecture and business by designing the buildings he develops.

His notable projects include 10 Sullivan Street, 456 West 19th Street, 508 West 24th Street, which is adjacent to the High Line, and 550 West 29th Street, also near the High Line. His designs use materials reminiscent of old New York, such as industrial steel windows, corbelled bricks, outdoor loggias, and oversized casement ribbon windows, however, he's not interested in mimicking existing architecture. Nor is he looking to create a "self-contained statement." Ahead, he discusses his career path, his inspirations, and the meld of architecture and development that he balances today.

In this article:

You have a chic industrial, yet classic style to your buildings and an “anti-iconic” philosophy. Is that your intention?

Cary Tamarkin: We like getting attention, but we don’t like screaming for it. When people talk about working with the neighborhood, that’s contextual design, purposely blending in, which is not exactly where we’re about either—although a lot of people will pass some of our buildings, and they’re not sure if they’ve been there for a long time or if they’re new constructions. We don’t try to mimic the buildings in the area, but it’s not a self-contained statement. We don’t aim for that. I’m surprised that after all this time, there’s a kind of signature to them. That didn’t start out with me saying, ‘this is what I want all the buildings to look like.’ But if you’re true to your ideals, there will be a similarity between them.

508 West 24th Street

508 West 24th Street

I think there’s a desire to strut your stuff, to show as much as you can, but that leads to all sorts of issues both urbanistically and physically.

Sometimes it’s appropriate, or it has no choice but to stand out among its neighbors, which have to take a step back — like the Guggenheim Museum that Frank Lloyd Wright did. That’s fine as far as urban design goes, to have a couple of statement buildings by talented people in the right spot. Like Frank Gehry’s building near the High Line. I don’t happen to be a personal fan of Frank Gehry although I think he’s a genius. Every time he does a building, it’s a statement building — though it’s getting to be the same statement building over again. But it doesn’t feel bad to me. What feels bad is lesser talented architects that just try and do tricks, but they don’t know how to do them as well. And there’s a lot of that because you don’t get many chances a year, much less in your lifetime, to build buildings. It’s a long, arduous process. So I think there’s a desire to strut your stuff, to show as much as you can, but that leads to all sorts of issues both urbanistically and physically.

How do you feel about the proliferation of the all-glass building?

Cary Tamarkin: I don’t know when the all-glass building became the model for a residential building. I’m looking across the street right now at an all-glass building, and I can see the backs of beds pushed against the walls in one apartment, a desk with a computer and wires coming down. It’s ridiculous. On paper, I’m sure it looks fine. The proportions are good. But glass doesn’t want to go down to the floor in a residential building. It’s hard to furnish or to live in.

You started out as an architect, and then turned to development. What prompted that decision?

Cary Tamarkin: I had a thought about eight or 10 years ago when it became a real fad for people to use Pritzker Prize-winning architects. I said to people in my office, this is crazy. We make no money doing architecture. We should use someone else for architecture and just be developers and make a bunch of money.

There’s the artistic side, which I love, and the business side that I love. I’m not out to do a million projects a year. I’m not out to do the biggest building in the world. I just want to do beautiful buildings, and there’s nothing I’d rather do than spend my time designing them; Put the family to bed, and then sketch until 2 or 3 in the morning. If I were just an architect, it wouldn’t be that enjoyable. I’d have to take a bunch of clients just to keep cash flow going. It’s a terrible business. It’s wonderful to do, but a terrible business. The great thing about doing both is that I don’t have to take any architectural job except my own.

There’s the artistic side, which I love, and the business side that I love. I’m not out to do a million projects a year. I’m not out to do the biggest building in the world. I just want to do beautiful buildings, and there’s nothing I’d rather do than spend my time designing them; Put the family to bed, and then sketch until 2 or 3 in the morning. If I were just an architect, it wouldn’t be that enjoyable. I’d have to take a bunch of clients just to keep cash flow going. It’s a terrible business. It’s wonderful to do, but a terrible business. The great thing about doing both is that I don’t have to take any architectural job except my own.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

I remember thinking, would I rather be designing a pool in the Hamptons or lying in my own pool in the Hamptons?

At around 35, I got the courage to consider not being an architect anymore, but it took 10 years to get mentally prepared to do that. I knew nothing about real estate development, so I had to learn. Now I’m responsible for multi-million dollar projects. I’m involved in the creative part and the business part. It’s a completely different business. I spend a lot of my time yelling, figuring out mathematical things, projecting into the future. Architects sit around and make beautiful things, and that’s what people count on you for. I’m really lucky. I tell people who want to go into the business end that the only real reason to do it is to make money. The only reason I don’t feel like a pig when I say that is that the first 35 years of my life were devoted only to art. But people love architects and hate developers. People love architects because they aim to change the world and make it beautiful. I really needed to prove to myself that I’m also a businessman. I remember thinking, would I rather be designing a pool in the Hamptons or lying in my own pool in the Hamptons?

Your style is a perfect match for the High Line. Now that 508 West 24th Street is sold out, what are your plans for 550 West 29th Street?

Cary Tamarkin: They’re two boutique buildings. There are no cookie cutter apartments. At 29th Street, every single apartment has 20-foot ceilings and tremendous walls of glass. It’s a new form of the signature stuff we’ve been doing. The real question is what do we do when we build outside of that zone, which we’ve only done twice. We’re doing a building on the Upper West Side, and we did a building on 91st and Madison, which also required a different aesthetic than downtown. The 29th Street building fits right into the portfolio of work on the High Line.

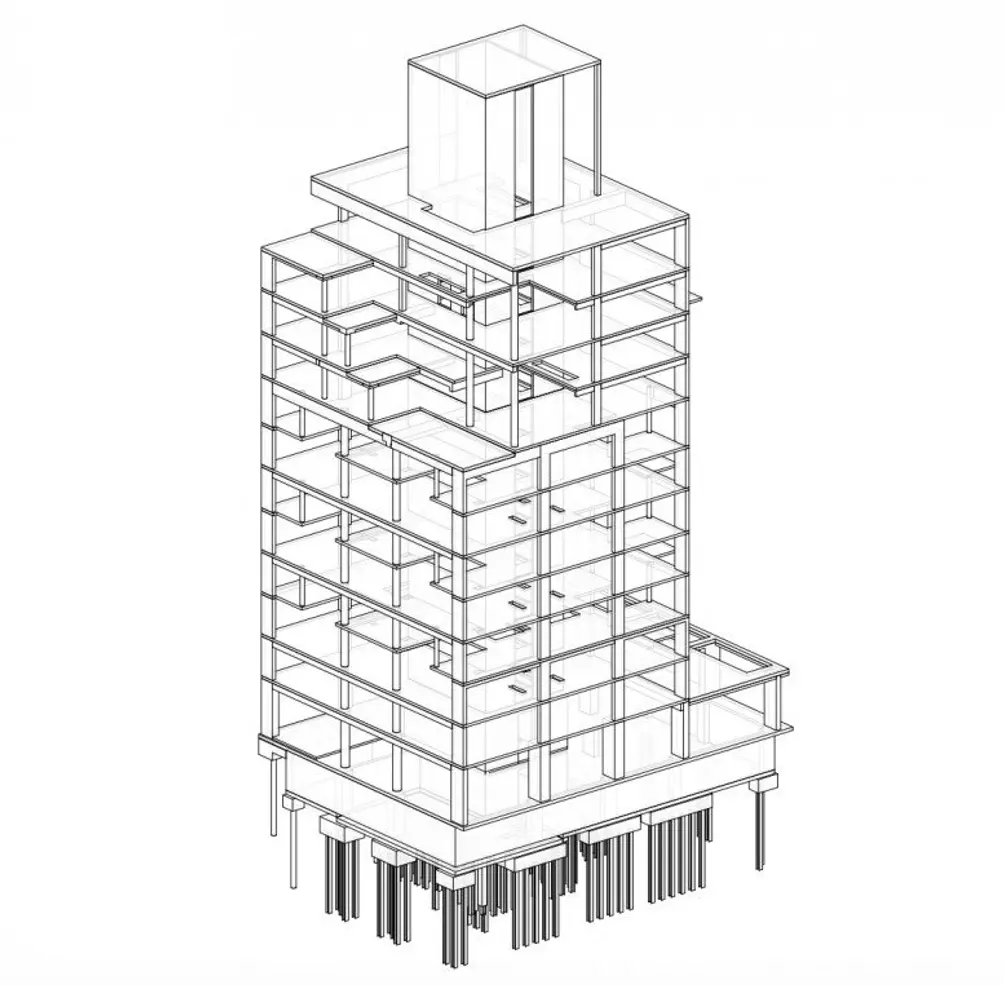

A preliminary drawing for 550 West 29th Street

A preliminary drawing for 550 West 29th Street

When you’re viewing a site to build from the ground up, what are you looking for?

Cary Tamarkin: The numbers that people are selling sites for now have gotten totally out of control. So the whole market’s changing. It doesn’t make sense, and there’s going to be a lot of collateral damage at the end of the cycle because there are a lot of new developers, and it’s a hard thing to do correctly. There’s acquisition prices, hard costs, construction prices. So the price of doing the whole building will not support the prices that you can get for the apartments when they’re done. So if I’m going to build anything in this environment, it’s got to be a great site.

A great site means a bunch of things. It could mean extraordinary views or on the river. We’ve done a couple of buildings like that. It could be an interesting place, like on a park for example. It could be in a zoning district or area that allows me to build with no height limit; I’d really like to do a tall building. It has to be unique, some place that we have a shot at making art. That’s what we try to do and make money while we’re doing it.

A great site means a bunch of things. It could mean extraordinary views or on the river. We’ve done a couple of buildings like that. It could be an interesting place, like on a park for example. It could be in a zoning district or area that allows me to build with no height limit; I’d really like to do a tall building. It has to be unique, some place that we have a shot at making art. That’s what we try to do and make money while we’re doing it.

In addition to being the architect of 10 Sullivan, you also did the interiors. Is the interior designer hat new for you?

Cary Tamarkin: I think of interior design as couches, chairs, and lamps. When I’m talking about about designing kitchens and bathrooms, I think of that as interior architecture. But on that project, I’m just the architect, not the developer, and that’s the first time I’ve done that. Bob Gladstone of Madison Equities, who owns the site, really wooed me. His vision was a romantic New York architect and he said, ‘You are that. You have to do this.’ It’s located on an incredibly prominent site because when you look up 6th Avenue, that’s what you see. The triangle shape was a little out of our comfort zone. It’s the building that’s iconic, and in will be over time, in that it welcomes you to Soho. It’s the tallest building that’s ever going to be in SoHo. It got a lot of attention. It fits in well with our portfolio. It reminded me of why I like having myself as the client.

Lastly, you renovated Anderson Cooper's firehouse. What was that project like?

Cary Tamarkin: That’s the same situation as the other houses, but it has the added celebrity factor, which is great. He is a delightful client. We looked at his previous apartment and it was done well, but very, very modern. It had walls that move by touching a button. So not Anderson Cooper. He hated that place. He never lived in it. So he bought this firehouse, and he and his partner wanted a very specific look. But if you look at our website, that’s not our look. But we got along great, and I came to understand the type of thing he was looking for. In the end, what he wanted was a firehouse, so the less we could make it look like an architect was there, the better. It was a chance to totally get out of our comfort zone. It was different from anything that we’ve ever done. We learned together how work with that building. I really love it.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Contributing Writer

Jillian Blume

Jillian Blume is a New York City based writer who has published articles widely in magazines, newspapers, and online. Publications include the New York Observer, Marie Claire, Self, MSN Living, Ocean Home, and Ladies Home Journal. Jillian received a master's degree in Creative Writing from New York University and teaches writing, critical reading, and literature at Berkeley College.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.