The Armory, #6S (Douglas Elliman Real Estate) | https://www.cityrealty.com/nyc/midtown-west/the-armory-529-west-42nd-street/apartment-6S/cXxRcRXAcwuN

The Armory, #6S (Douglas Elliman Real Estate) | https://www.cityrealty.com/nyc/midtown-west/the-armory-529-west-42nd-street/apartment-6S/cXxRcRXAcwuN

Anyone new to New York City’s housing market soon learns that “flex” doesn't refer to an apartment with muscle but rather to a studio, one-bedroom or two-bedroom unit large enough to be converted up one level with the addition of a pressurized wall.

For roommates and a growing number of couples and families, especially in Manhattan, the flex is often pursued as an alternative to moving to an outer borough or leaving New York City altogether. After all, even in the current crazy rental market, it may be possible to find a flex one-bedroom in a full-service building south of 96th Street in the $3,750 per month range. But finding a comparable two-bedroom unit in this price range and location is highly unlikely. For couples, the potential to flex a unit, whether it is rented or owned, is also appealing, since it means the option to stay exists if or when they decide to start a family.

Unfortunately, while many apartments are advertised as flex, over the past decade the ability to legally flex an apartment has become increasingly difficult as city officials, building inspectors, management companies and co-op boards have sought (not necessarily for the same reasons) to put an end to New Yorkers’ love affair with the flex.

For roommates and a growing number of couples and families, especially in Manhattan, the flex is often pursued as an alternative to moving to an outer borough or leaving New York City altogether. After all, even in the current crazy rental market, it may be possible to find a flex one-bedroom in a full-service building south of 96th Street in the $3,750 per month range. But finding a comparable two-bedroom unit in this price range and location is highly unlikely. For couples, the potential to flex a unit, whether it is rented or owned, is also appealing, since it means the option to stay exists if or when they decide to start a family.

Unfortunately, while many apartments are advertised as flex, over the past decade the ability to legally flex an apartment has become increasingly difficult as city officials, building inspectors, management companies and co-op boards have sought (not necessarily for the same reasons) to put an end to New Yorkers’ love affair with the flex.

In this article:

Unfortunately, while many apartments are advertised as flex, over the past decade the ability to legally flex an apartment has become increasingly difficult...

Image: www.wall2wallny.com

Image: www.wall2wallny.com

When the Walls Went Up...and Started to Come Down

While the origins of the flex are difficult to trace, the term gained traction in the early 2000s as rents soared and a growing number of New Yorkers started searching for innovative ways to keep growing in their existing units or to break into the housing market for the first time. The rise of the flex initially went more or less unnoticed by officials. Following a fatal 2005 fire in the Bronx, however, temporary walls started to come under heightened scrutiny. As a subsequent investigation revealed, these walls were largely to blame for the loss of lives in the Bronx fire, since the walls had made it impossible for first responders to effectively navigate the building.In turn, city officials, owners, management companies, co-op boards and insurance companies started to crackdown on pressurized walls. While safety concerns topped city officials’ concerns, management companies became increasingly concerned about the liabilities associated with permitting flex units. Co-op and condo boards also started to place restrictions on flexing, but often in an effort to ensure that smaller units did not become home to multiple residents who place greater pressure on facilities and staff. While some buildings demanded that existing walls come down, in other buildings, existing walls were permitted to stay up but new walls were not permitted. This resulted in a hodge-podge of rules, regulations and contradictions regarding flex apartments, which continues to confound renters, buyers and even brokers to this day.

What is a legal bedroom in NYC

In New York City, a room must meet strict criteria to be considered a legal bedroom. It must be at least 80 square feet in size, with no dimension under 8 feet, and have a ceiling height of at least 8 feet (7 feet in some basement cases). A legal bedroom must also include a window that opens directly to a street, yard, or court, with the window area equal to at least 10% of the room’s floor area and at least one window measuring 12 square feet or more. The window must also be operable to provide ventilation.Additionally, every bedroom needs two means of egress, such as a door and a usable window, and it cannot be accessed only by walking through another bedroom. Because of these rules, spaces without proper windows or emergency exits, like interior “sleeping lofts” or windowless alcoves, cannot legally be called bedrooms, even if they’re commonly used as such.

How to Avoid Renting or Buying a False Flex

Karen Lockhart, who lives with her husband and 12-year-old daughter in a 610-square-foot apartment in an Upper East Side co-op, is among the New Yorkers who has found herself navigating the muddle of rules that now governs flex units. “When we rented in 2012,” she recalls, “The broker assured us we could flex the unit. Still, I called the management company to confirm. Again, the manager assured me that the apartment could be flexed, since they owned two other units in the building with pressurized walls.” Yet, when Lockhart informed her building’s superintendent that she had hired a contractor, she learned that the building’s board no longer approved pressurized wall. In the end, Lockhart was able to get around the co-op’s rules by installing a shoji wall with a “floating” frame (a convenient, albeit usually more expensive, way to divide an apartment while meeting fire and building codes).When considering a flex, make sure you ask these questions upfront:

- Even if the apartment is advertised as a “flex,” don’t assume you can legally install a wall. Before signing any papers, confirm that all interested parties agree that a pressurized wall can be installed. If you’re renting from a management company, confirm that your management company and your building’s superintendent (and where applicable, co-op or condo board) will approve the installation. If you’re buying, clear the proposal with the building’s superintendent and board.

- If you hope to gain approval for a wall prior to renting or buying, know where the wall will be installed and who will likely be contracted to carry out the work. Bear in mind that if you’re looking to add a bedroom, it will need to meet the legal definition of a bedroom as defined by the New York City Housing Authority (in a one- or two-bedroom unit, the room will need to occupy at least 80 square feet of floor space and have at least one regulation-size window).

- Even if a wall can be installed, carefully consider whether or not flexing the unit will meet your needs. What are your priorities? Soundproofing or light? In an ideal world, no one would be forced to choose between these two seemingly essential features, but this is New York City where housing compromises are a way of life. While a pressurized wall offers better soundproofing, depending on the availability of windows, the wall may block out most or all of apartment’s natural light. If light is a priority, a sliding shoji wall may be preferable.

- What is the likely long-term return on investment? If you’re an owner, consider whether or not the wall will add value to your apartment or create a cramped and dark space that may reduce your unit’s resale value. If you’re a renter, consider whether or not the cost of installing a wall, which will likely run between $3,000 to $10,000 depending on the type and size, can be recuperated. Renters may also want to consider the relative benefits of investing in a more expensive sliding shoji wall, which can be moved and remodeled, versus a pressurized wall that will become a permanent feature of the apartment.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Spacious Studios That Feel Like One-Bedrooms

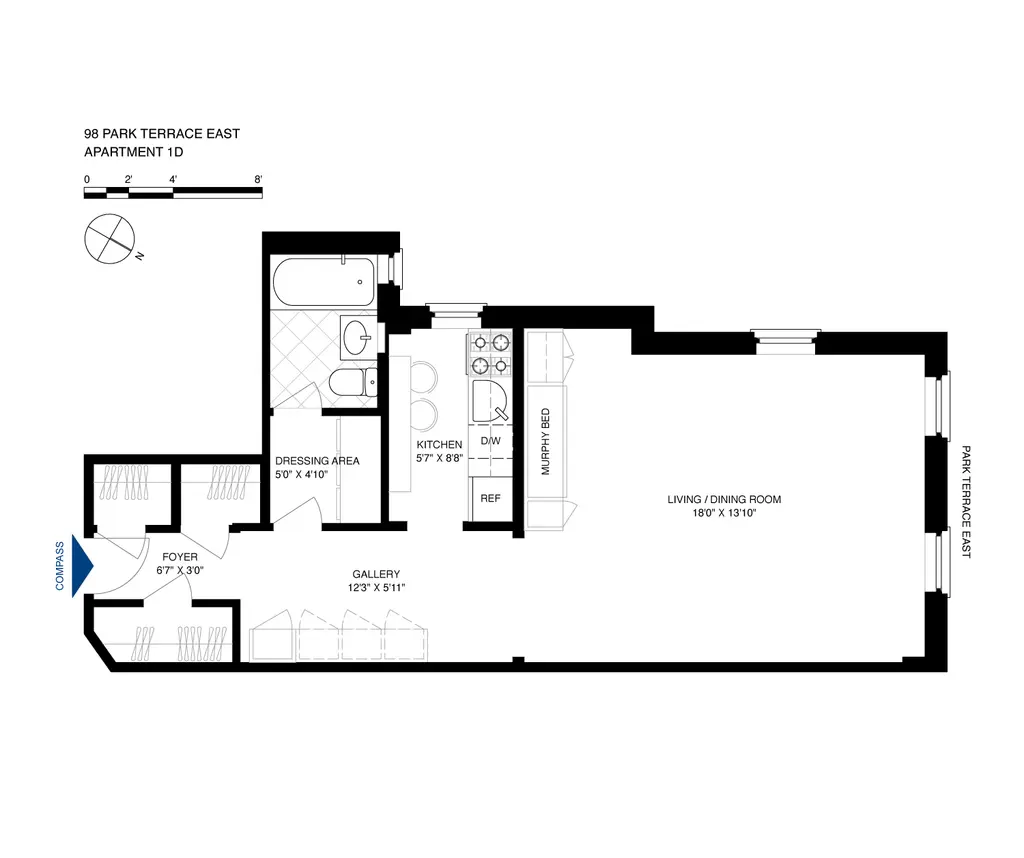

98 Park Terrace East, #1D (Compass)

The Parc Vendome, #3J (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

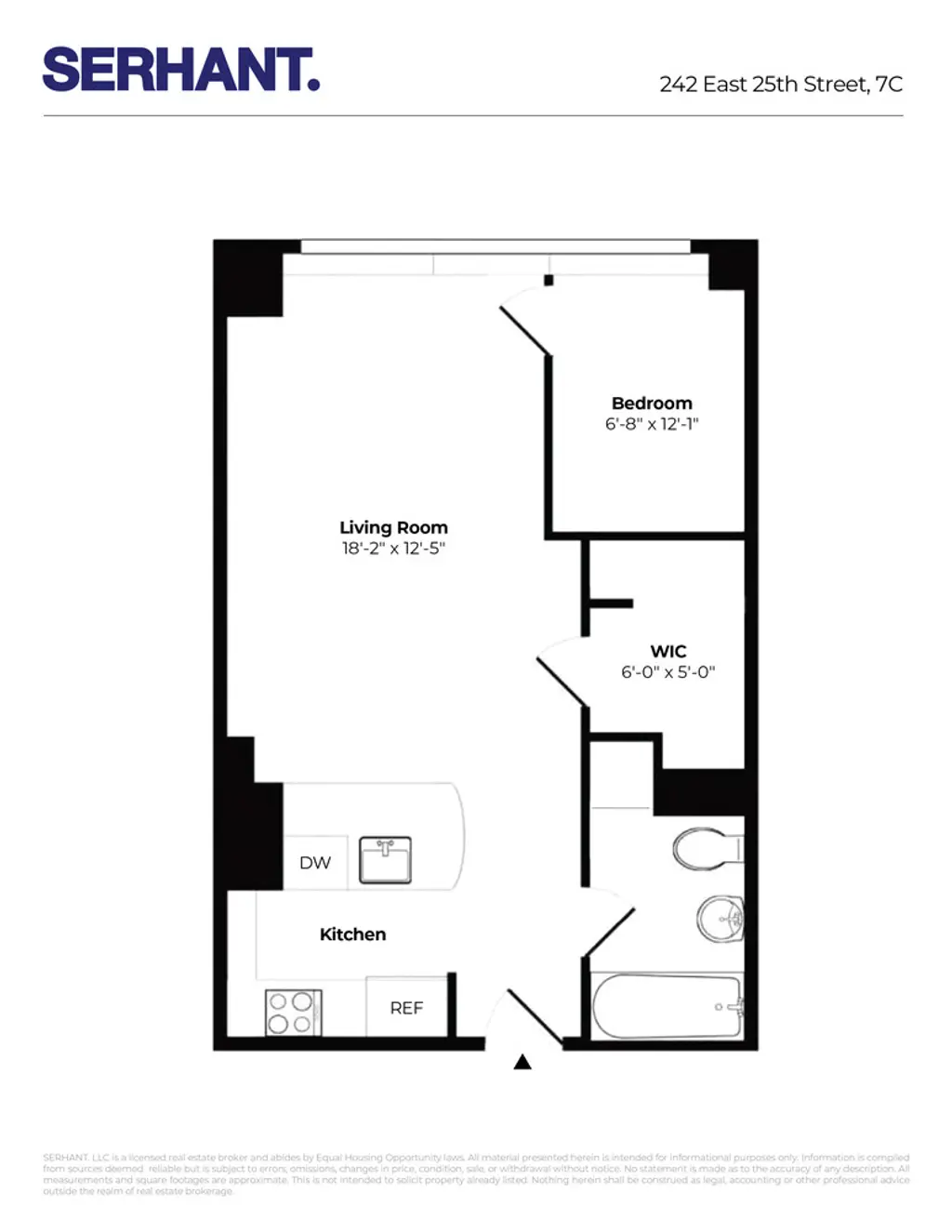

242 East 25th Street, #7C (Serhant)

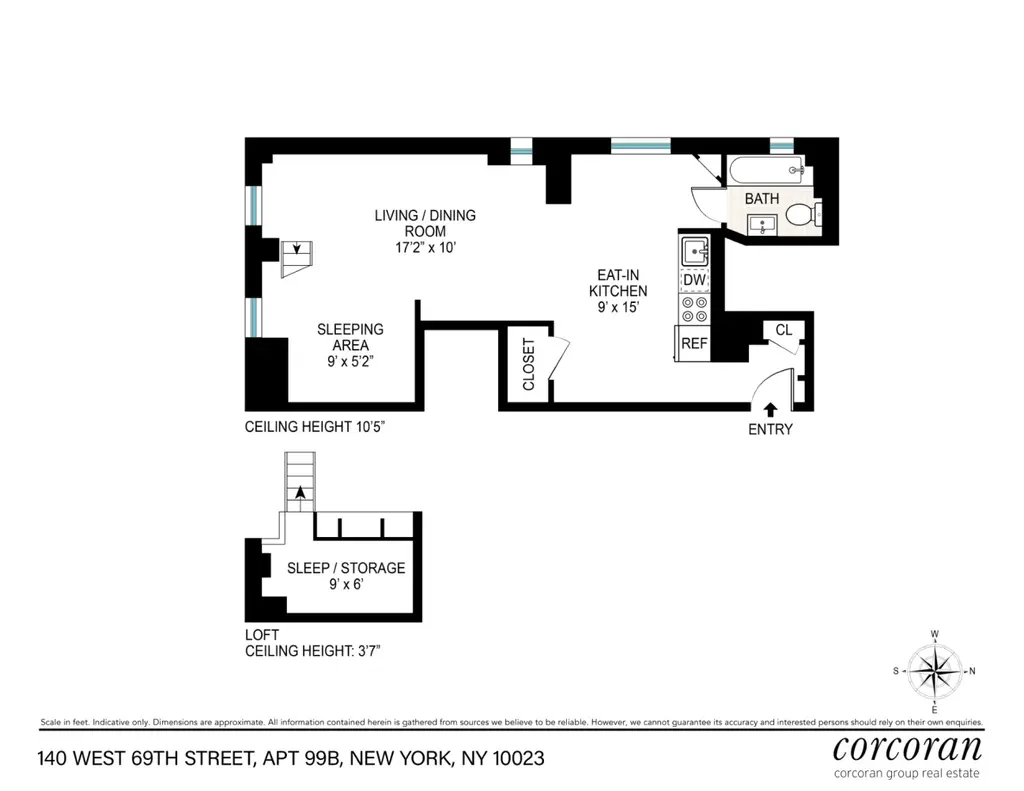

Lincoln Spencer Arms, #99B (Corcoran Group)

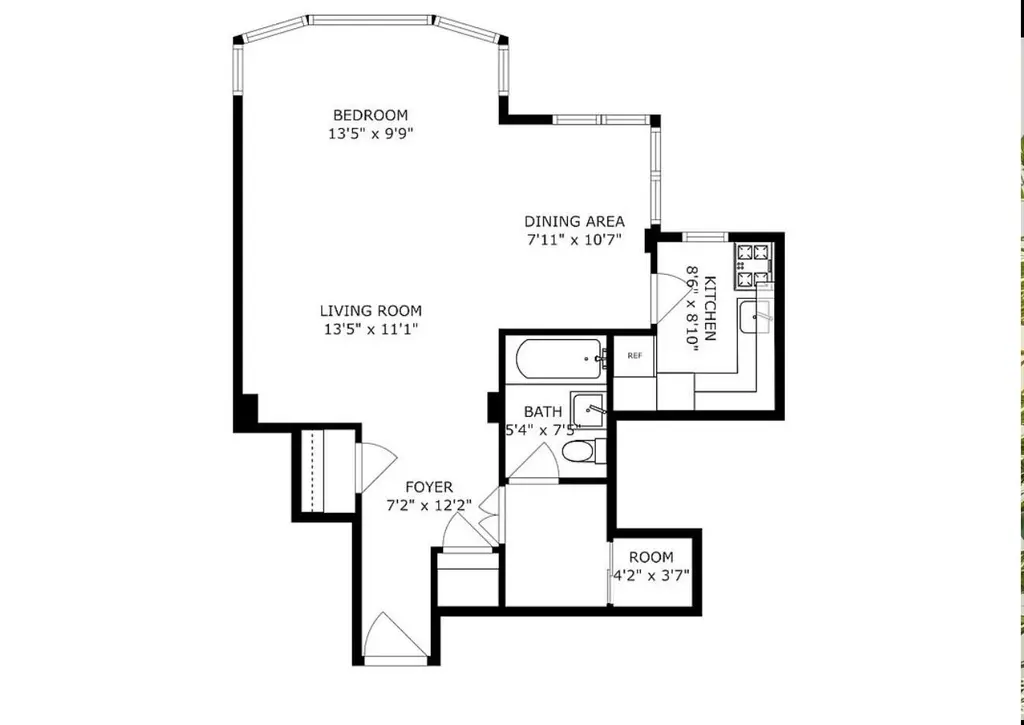

Sutton Manor, #10C (Buchbinder & Warren Realty Group LLC)

The New York Towers, #4L (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

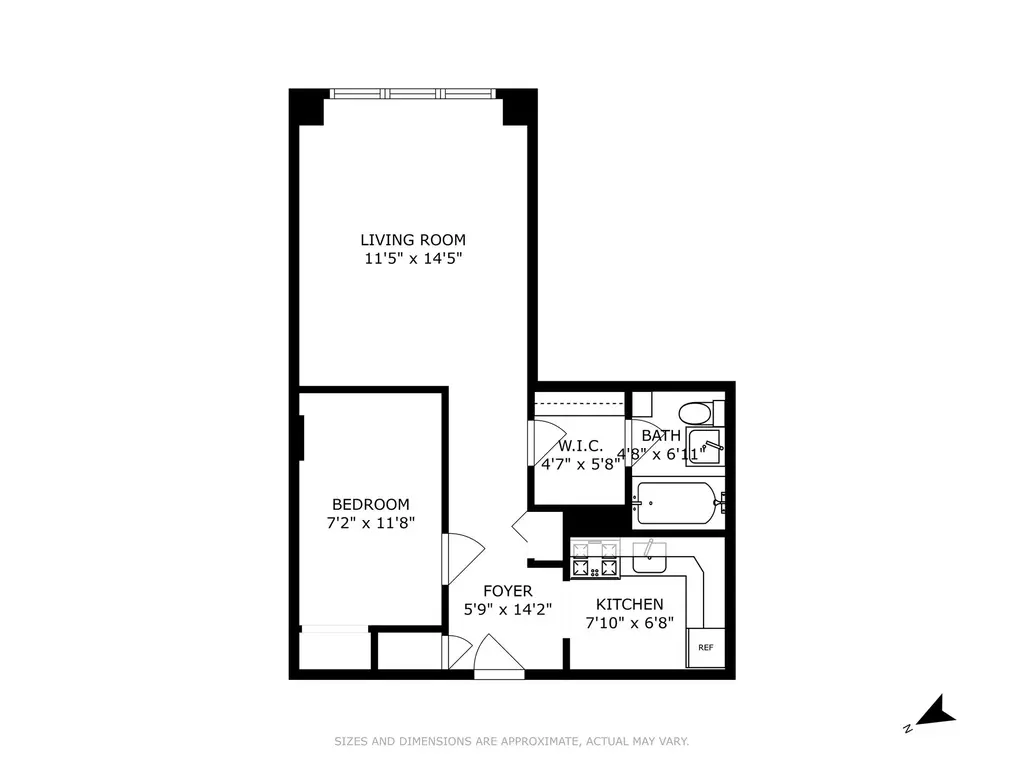

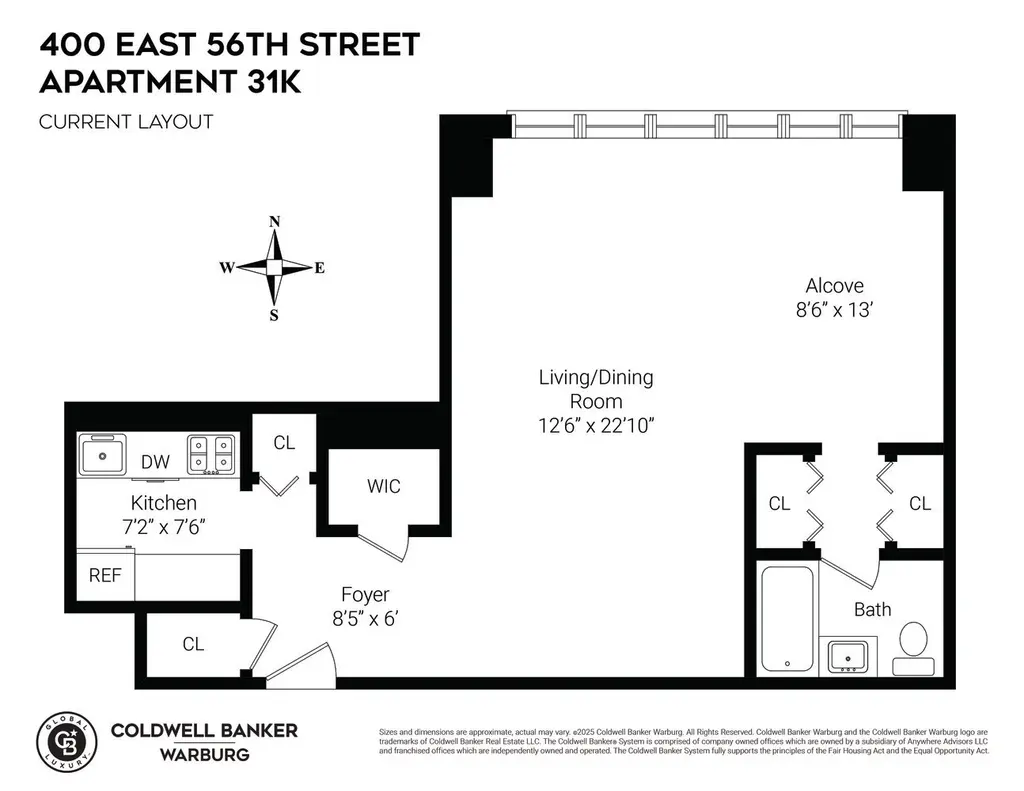

Plaza 400, #31K (Coldwell Banker Warburg)

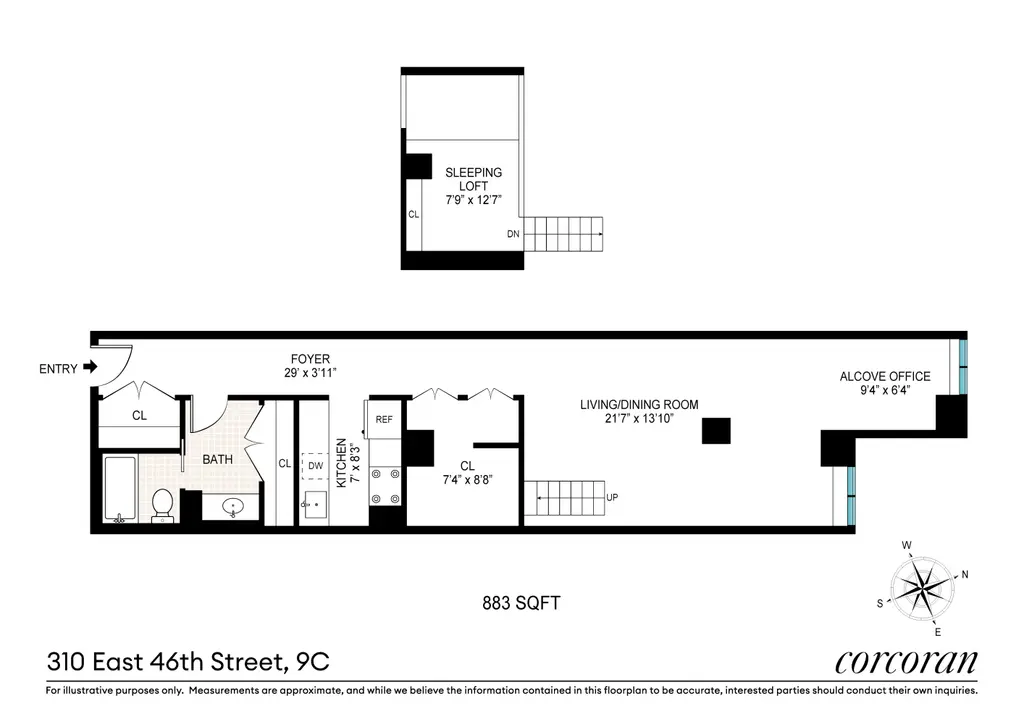

Turtle Bay Towers, #9C

$650,000 (-5.1%)

Turtle Bay/United Nations | Condop | Studio, 1 Bath | 733 ft2

Turtle Bay Towers, #9C (Corcoran Group)

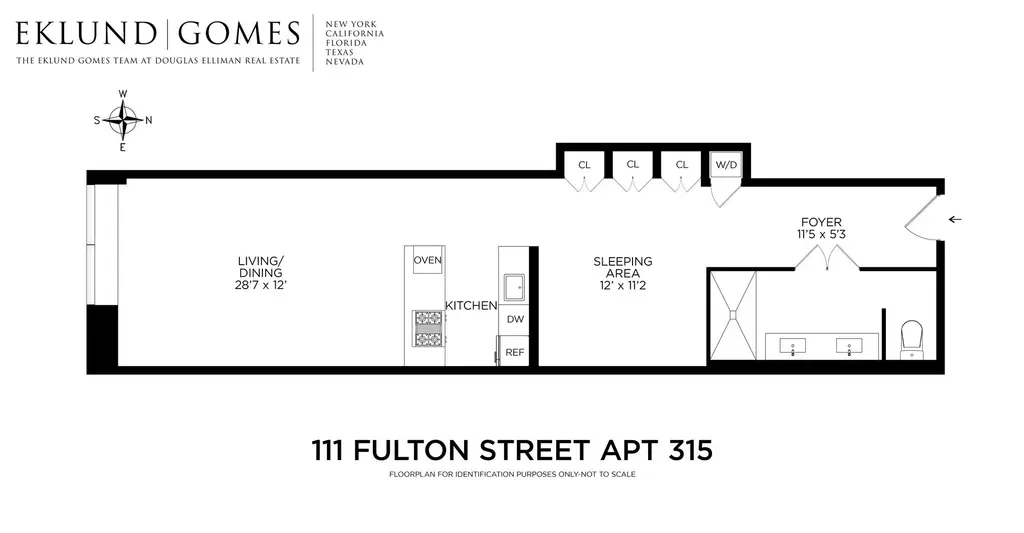

District, #315 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

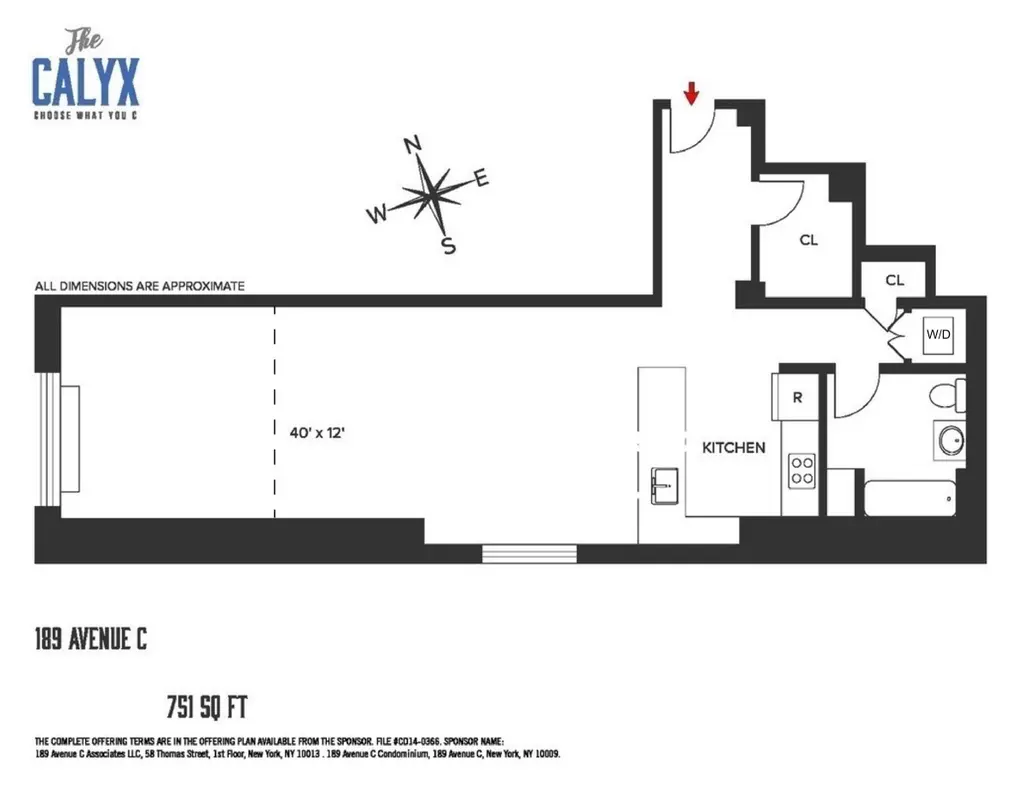

The Calyx, #4D (Compass)

The Platinum, #401 (Blu Realty Group)

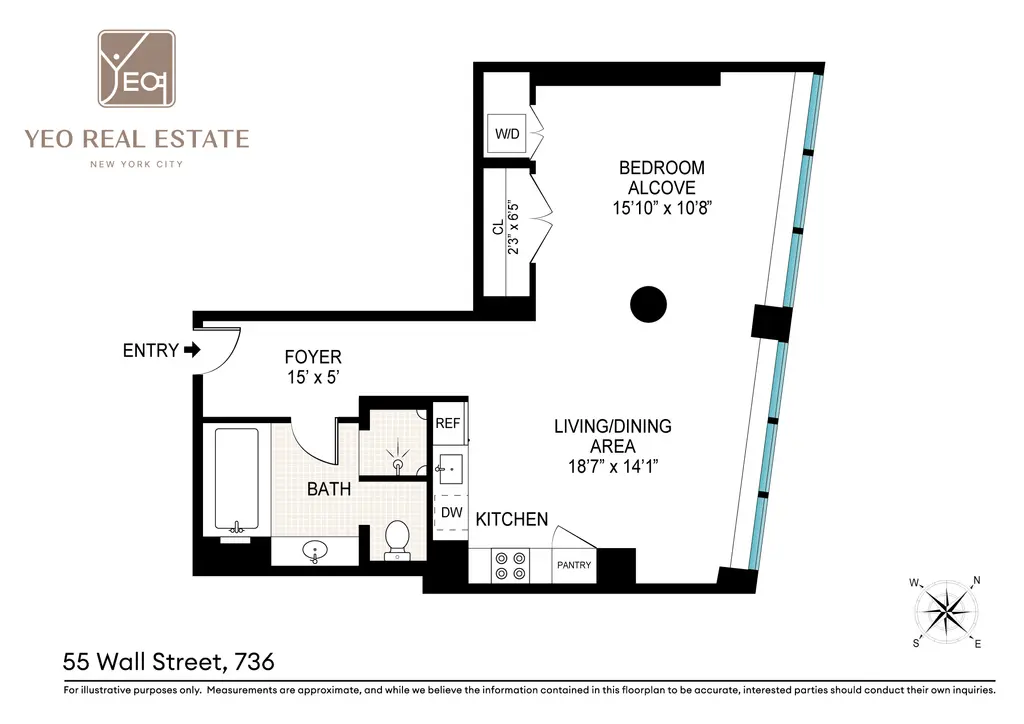

Cipriani Club Residences, #736 (YEO REAL ESTATE LLC)

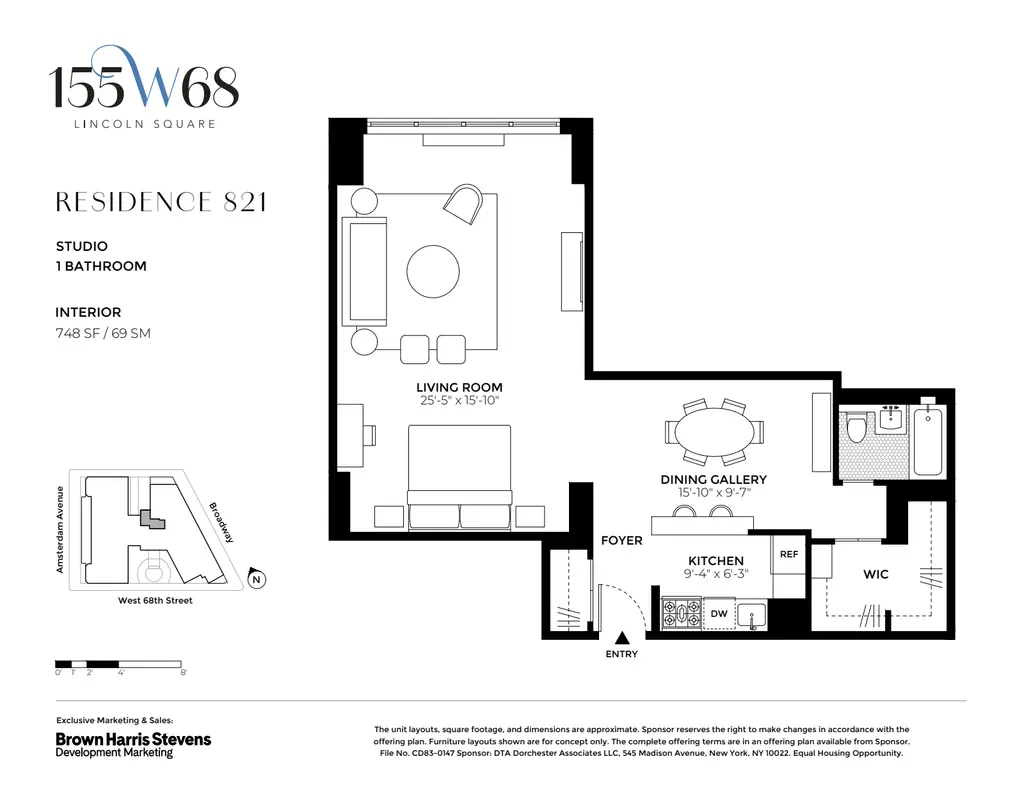

155W68, #821 (Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing LLC)

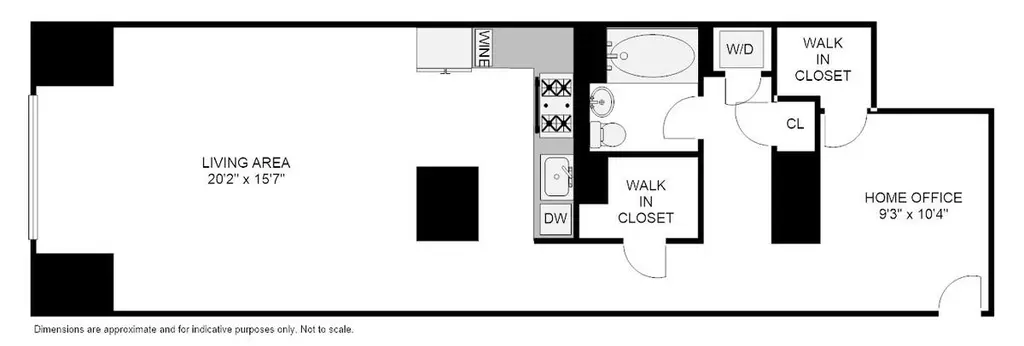

99 John Deco Lofts, #2210 (Elegran LLC)

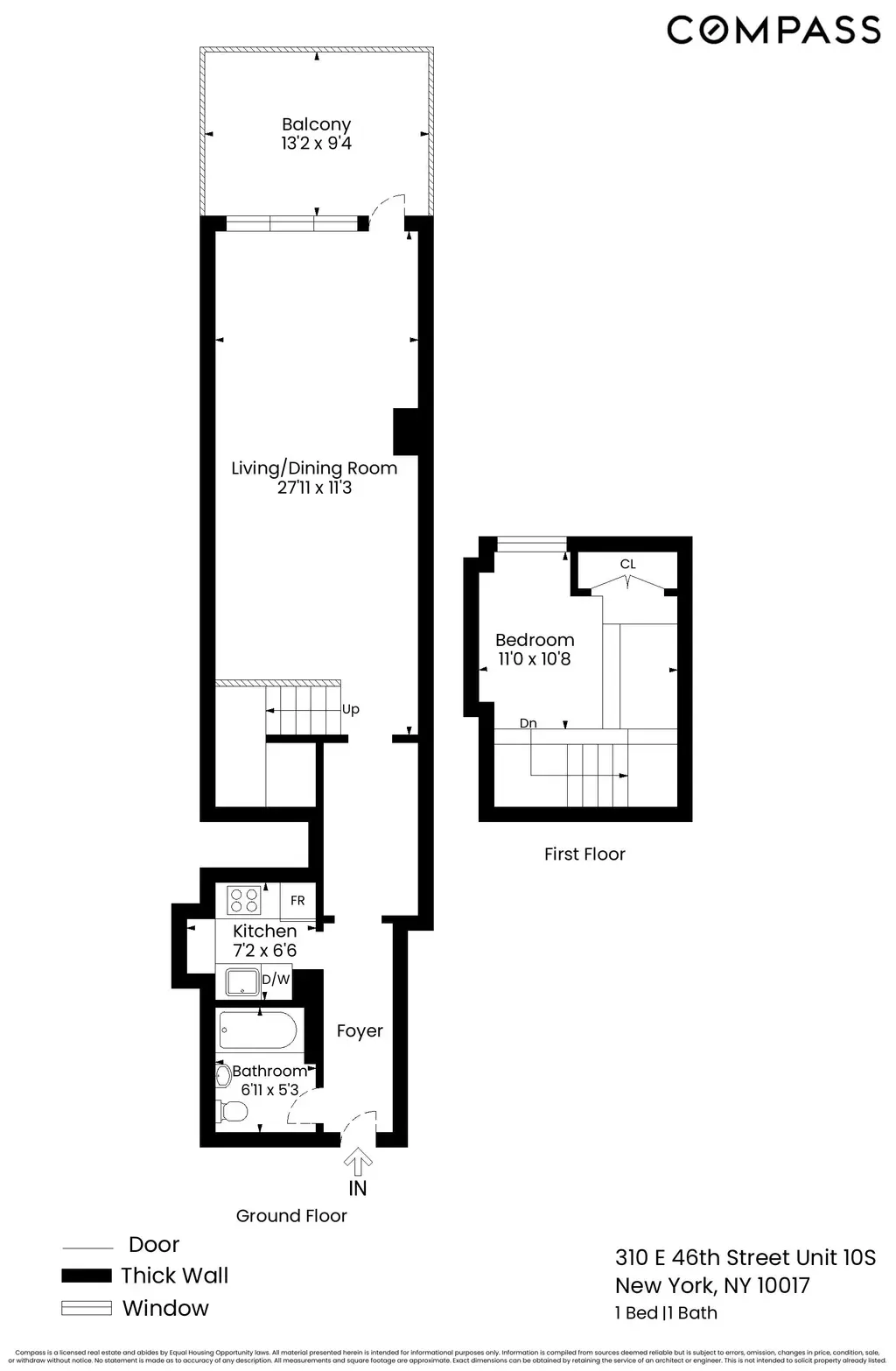

Turtle Bay Towers, #10S (Compass)

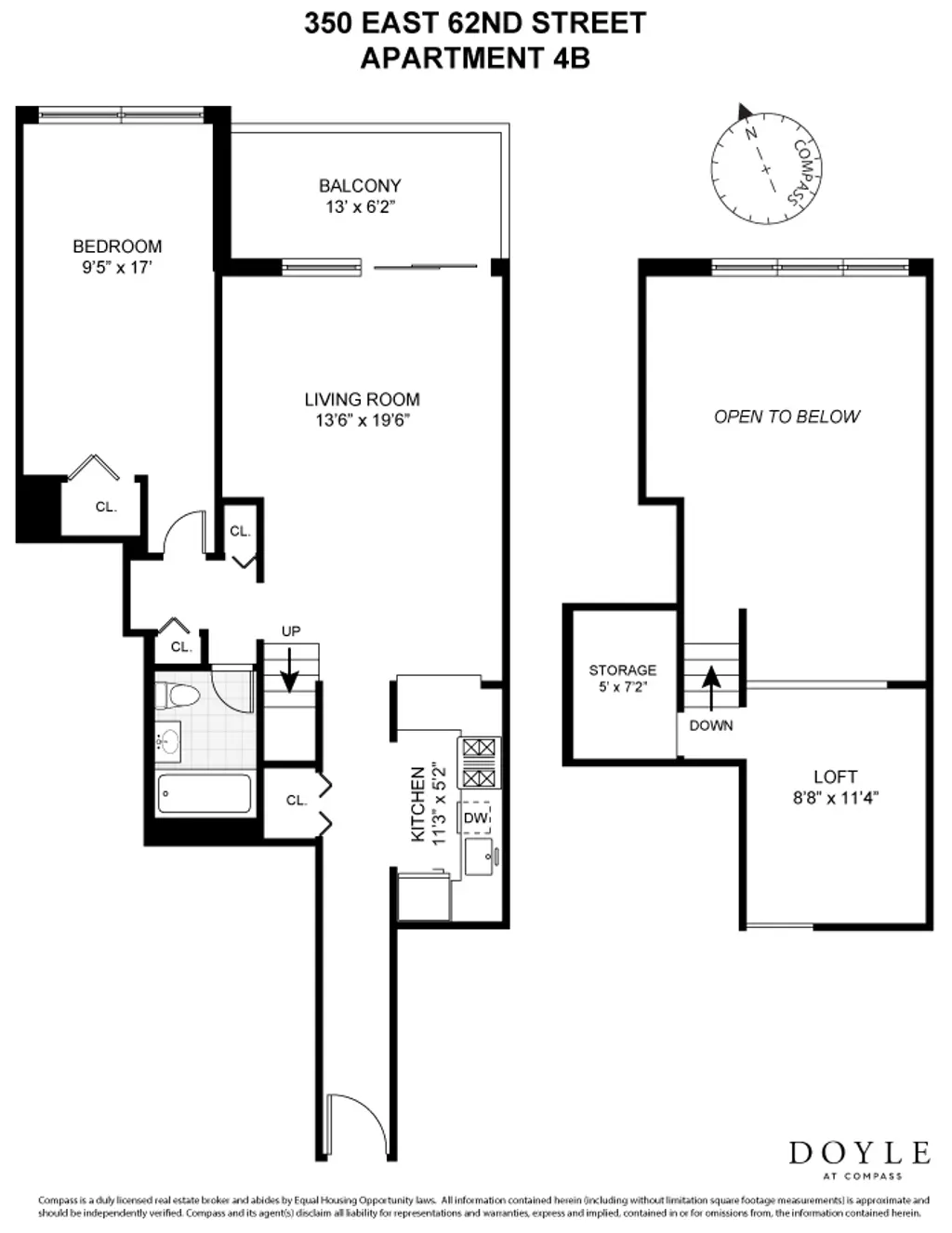

The Beekman Condominium, #4B (Compass)

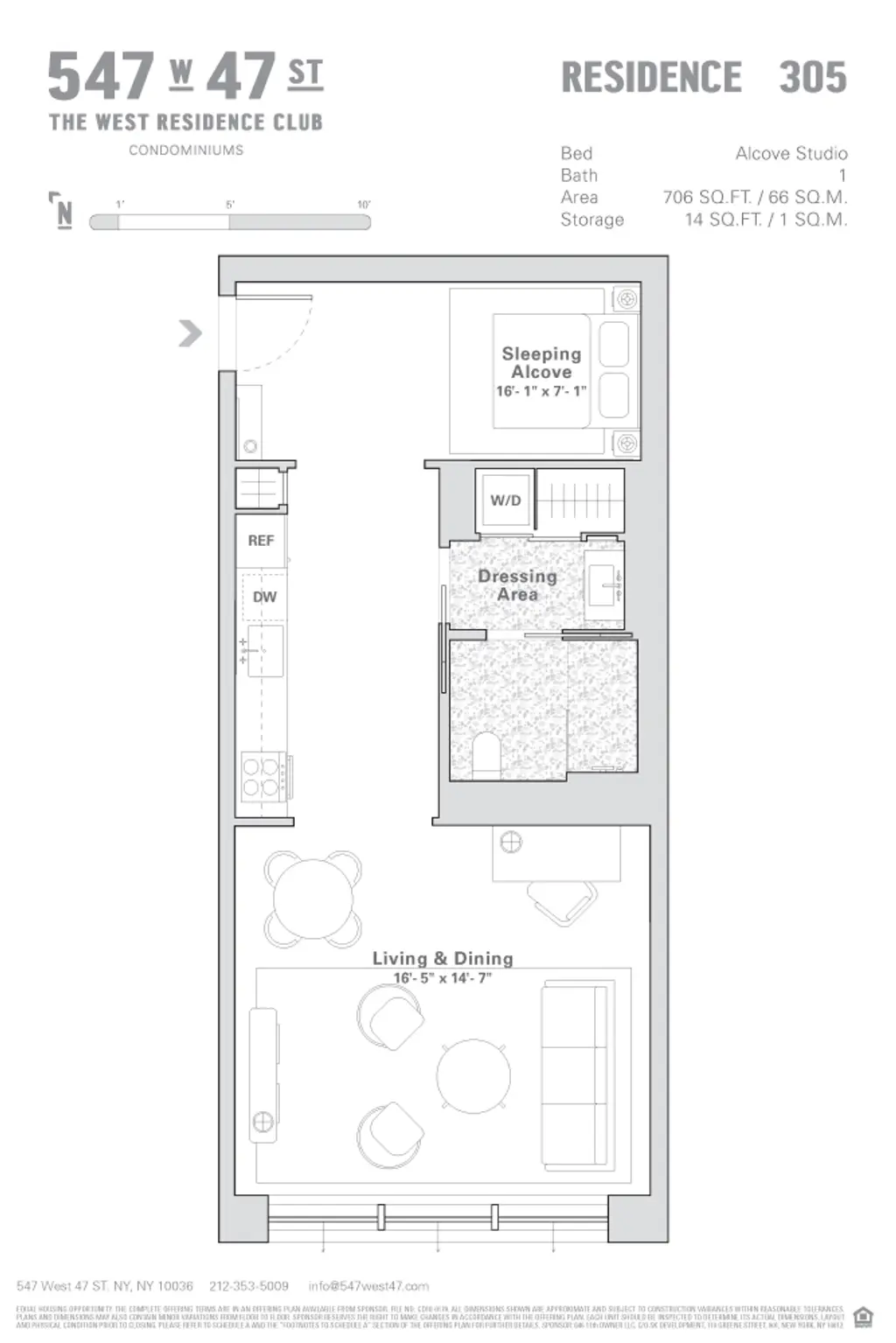

The West Residence Club, #305 (Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group)

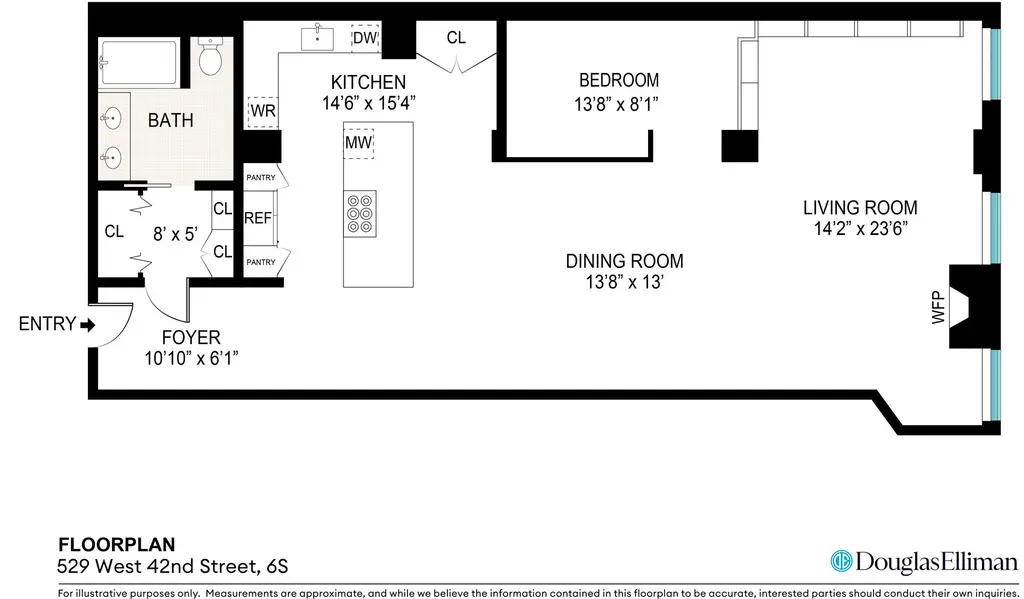

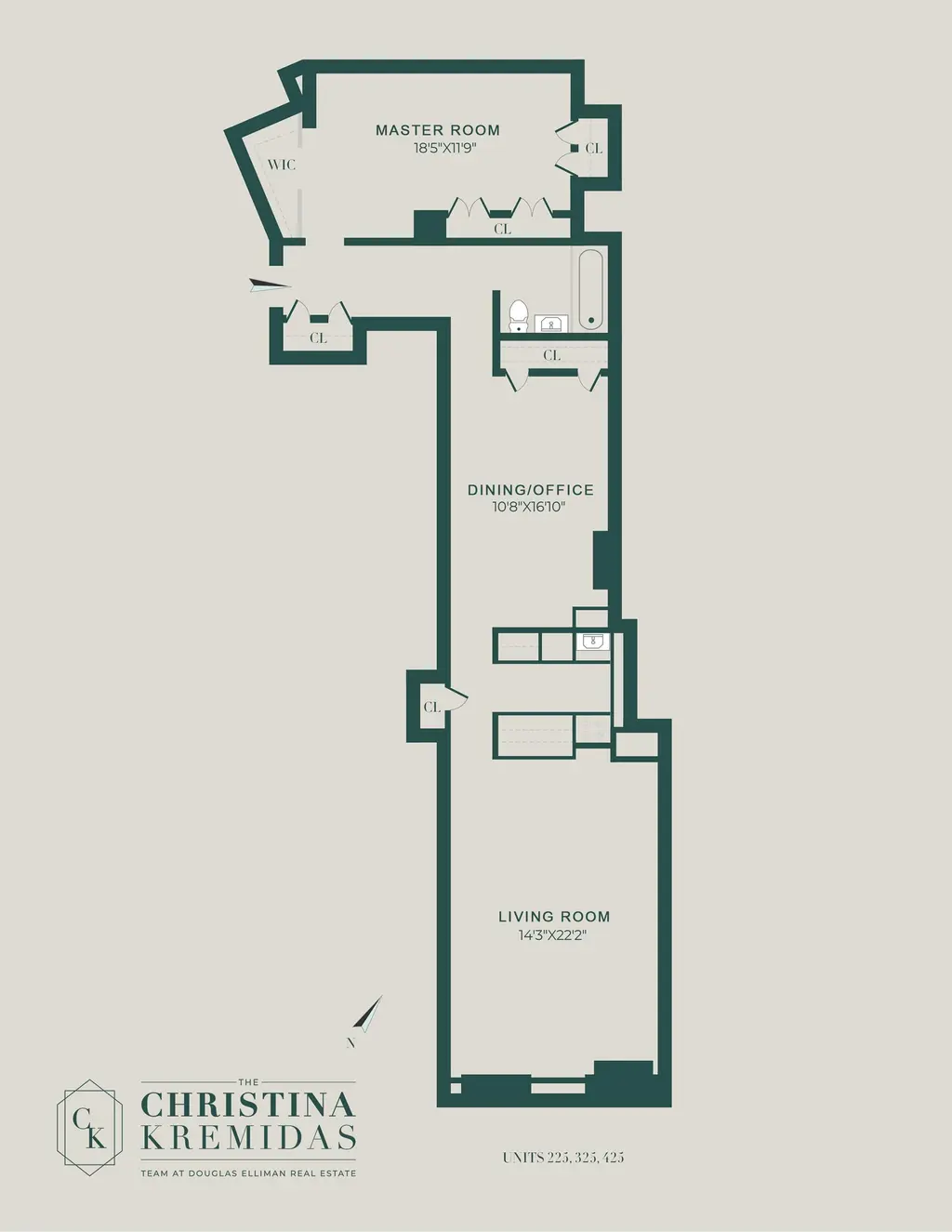

The Armory, #6S (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

15 William NY, #12D (Corcoran Group)

99 John Deco Lofts, #425

$995,000 (-9.5%)

Financial District | Condominium | 1 Bedroom, 1 Bath | 1,096 ft2

99 John Deco Lofts, #425 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Halcyon, #4E (Sothebys International Realty)

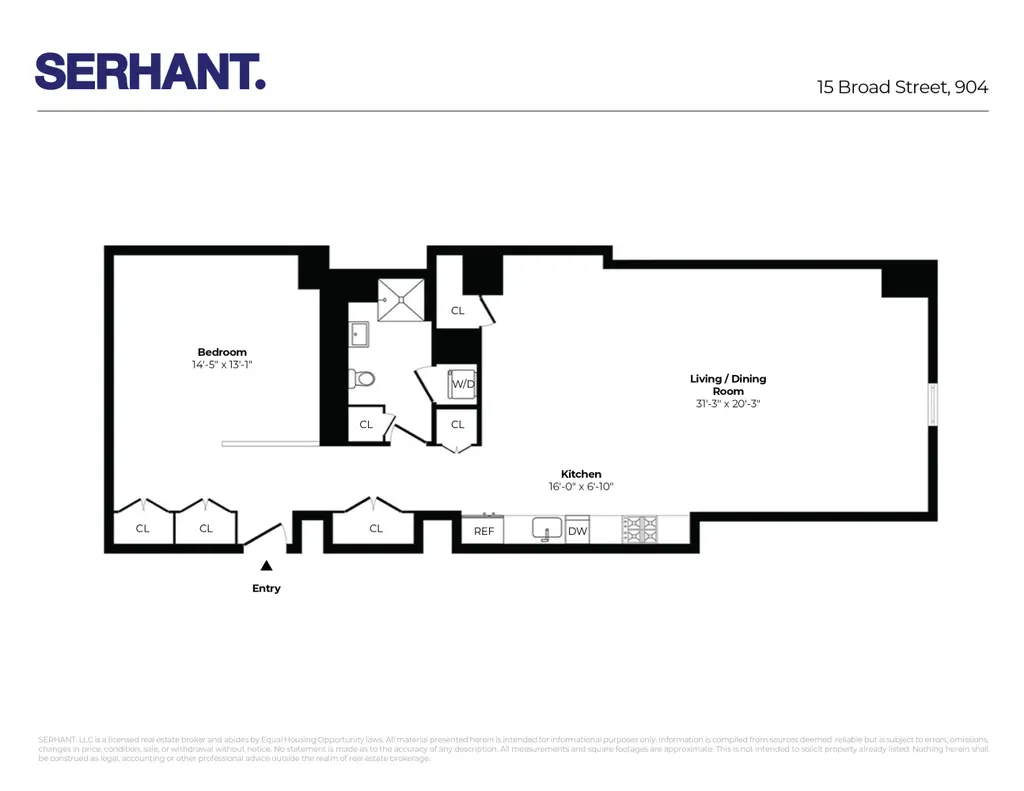

Downtown by Starck, #904

$999,999 (-16.7%)

Financial District | Condominium | 1 Bedroom, 1 Bath | 1,200 ft2

Downtown by Starck, #904 (Serhant)

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Contributing Writer

Cait Etherington

Cait Etherington has over twenty years of experience working as a journalist and communications consultant. Her articles and reviews have been published in newspapers and magazines across the United States and internationally. An experienced financial writer, Cait is committed to exposing the human side of stories about contemporary business, banking and workplace relations. She also enjoys writing about trends, lifestyles and real estate in New York City where she lives with her family in a cozy apartment on the twentieth floor of a Manhattan high rise.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.